“Having transcended the seven evolutionary superuniverses of time and space which circle the never-beginning, never-ending creation of divine perfection, Murphy arrives at the heart of the eternal and central universe of universes on the stationary isle of paradise, the geographic center of infinity, and the dwelling place of the eternal living God! It is here that our story opens…” —Murphy, Surfer magazine, May 1969

Indian Summer, 1963. Dawn. Crow caw, smell of onions. Highway 101, a shoulder-less two-lane blacktop, snakes its way through the wind-cowed Salinas Valley. To the east, the morning sun throws a few lackadaisical red rays over misty tracts of broccoli and iceberg lettuce. Near the packing sheds, sleepy braceros stamp chilled feet like horses and gingerly sip steaming cowboy coffee from blue metal cups. The bucolic hush is punctuated by the occasional scree of a red-tailed hawk nesting the gnarled eucalyptus windbreaks overlooking the highway north of King City, population 894.

From the distance, a deep-throated grumble of a 1950 Plymouth coupe gunning down the highway. The sound builds, thundering crescendo, a sudden squeal, the sharp pop of a door latch releasing and fat Goodyear whitewalls skid by, trailing a slipstream of dust and cheap gaudy carnival trinkets. Floating in the haze is a surreal tableau of vintage 10-cent gimcracks: kazoos, Kewpie dolls, Groucho glasses, tin cricket clickers, hula girls, piggy banks, Chinese finger traps, whoopee cushions, Bakelite puzzles, and little grinning see-no-evil smoking monkeys.

A small wooden artist’s sketch box spins through the toys, revolving end-over-end, in slow motion. It strikes the asphalt and explodes. Brushes, paints, and charcoal pencils cascade in lovely chaos across the highway. A single, silver, double-aught Rapidograph drafting pen hovers in space, spinning like a propeller.

Rick Griffin, handsome, towheaded 19-year-old surfer from Palos Verdes, sails through the air. He’s wearing regulation early 60s surfing garb: Levis, white Jack Purcell low-cut tennis sneakers, and a gray plaid Pendleton over a road-stained JC Penny t-shirt. He is suspended, caught in this moment forever. Beardless youth, shock, arresting blue eyes bulge in horror.

Click…a house party back in Torrance. Lots of kids, surfers, greasers, girls, a keg. “Mr. Moto” pulses from the portable Symphonic 45. He’s laughing, dancing. A flash of sunburned thighs, a girl’s delighted high-pitched squeal. His girl, a honey-skinned Mexican beauty, across the room, sulking, glaring.

Click…his mother, Jackie, stern and German, shouts at him as he tears out the door. “If you stay out all night again, don’t bother coming home!”

Click…the party’s over. His buddy Tom and him finish off the keg, sit in the ochre light at the kitchen table. A recent issue of Surfer opened to blue warm waves. Australia, a new land. A finger traces a line of longitude on a borrowed globe. A plan: hitchhike to San Francisco, catch a freighter, working passage, why not? A defiant slosh to freedom.

Click…evening, Malibu, Pacific Coast Highway. Clammy sea mist, no ride since sundown, exhaustion, hangover. Tom sleeps in the bushes. Rick squints at a set of headlights, a rumble, a crunch of gravel, a resting gap-toothed grille. Roy Orbison wails through the dashboard. A whiskey-soaked voice beckons: “Hop in boys!”

Click…a small wiry man, hard used, chain smoking, stained teeth, a carny. Runs the ring toss and the shooting gallery. Boxes of prizes piled on the seat and floorboard. Nonstop amphetamine chatter, carny talk. “Heezoly sheezit!” Loves Kentucky bourbon, loves poozle, loves sweet delta blues, you see. Driving all night to make an afternoon show in Petaluma. “Gotta sweet little thing going up there…she’s a midget, you understand…”

Click…Rick riding shotgun, finally warm, lulled to sleep. Daybreak, farm fields, hears the carny, ratcheting on: “Yessir, this Special Dee-lux version is one of the finest machines ever built…a Chrysler L-Head straight-six with crackerjack suspension. Why I could take my hands off the wheel and this baby would steer itself straight as an arrow…”

Click…a sickening lurch to the left, over-correction to the right, the carny cursing. “Jay-sus!” The car goes into a long arcing skid, irresistible tendrils of centrifugal force pulling at him…

Click…Rick floats over the highway, wind billowing his Pendleton, a blur of picketing white lines, a whirring black grindstone, bearing down, stringy-bark eucalyptus, smell of onions…

Searing flames on his cheek, flesh rendering, then darkness.

In the darkness, gliding, speeding along the edge of a vortex. He feels his fingers drag along a spinning wet wall. Wraithlike wail of the tube, a hollow exhalation. He knows this place. A faint light ahead, grows stronger, a roaring hiss…

Click.

Rick awakes swaddled in a pink morphine cloud. A young woman’s voice, clear and monotonous, reads the 23rd Psalm. His left eye is taped closed. He opens his right and sees only a gauzy red veil. Sounds of a hospital. Muzak, sharp clink of polished sterilized steel dropping into a metal pan. A man’s voice, tired, plaintive: “C’mon Bill, let’s go to lunch. That kid’s a goner.” Rick, panicked, aghast at the prospect of being buried alive, tries to scream but finds his jaw is wired shut.

Click…

That’s one version. Over the years, Rick’s accident has become a sort of Chinese chain letter. Some versions have him hitchhiking solo, some with a high-school friend named Tom. Others have him driving the car and picking up a mysterious hitchhiker whom he lets drive. Others have him rolling the car, this time a 1954 Ford station wagon. Another variation has him going through the windshield and the car rolling over him. Another has him in a friend’s Corvair hitting a bridge abutment in Rosarito. Yet another has his friend, frying on acid and driving a sports car at night, swerving to avoid a ghost child standing in the road.

This isn’t surprising. Griffin actively cultivated conflicting, often warring personas throughout his life, not unlike his cartoon alter ego Murphy. Both were open to creative embellishment or wholesale editing by others until they were ready for print. Each of his family and friends nurture a cherished rendering of Rick that they protect jealously from dissenting accounts.

“Griffin was never into moderation,” says Steve Pezman, who knew Griffin from the mid-60s. “He kept trying on answers and assumed that persona. When he’d come into Surfer when I was the publisher, I never knew which Rick Griffin was coming in. He’d ride up on a Harley and all the secretaries in the building would be looking out the windows going, ‘God, who’s this guy?’ It was just a sight to behold.”

Various descriptions include, but aren’t limited to: gas-huffing Lakewood pachuco, guileless pretty-boy gremmie, Haight-Ashbury charismatic, goofball Christian dad, beatnik art student, underground-comic pioneer, clueless womanizer, middle-aged punk rocker, psychedelic poster art legend, ill-tempered prima donna, luckless good guy, hog-riding-crack-smoking-rock-star-wannabe.

But mostly, it seems, Rick Griffin was a surfer. And an artist.

This much of the accident, however, can be triangulated from a short bulletin published in the “Surf Spots” gossip column of the December-January 1963 issue of Surfer: “On Monday October 7, Surfer cartoonist Rick Griffin was seriously injured in an automobile accident while traveling through King City. Rick’s situation was extremely critical for several days with his life hanging in the balance. As we go to press, it appears that he will live.”

There are no further details. But the note, almost certainly written by Surfer’s then publisher John Severson, signs off with a heartfelt get-well and a subliminal challenge for Griffin. “It’s going to take a lot of courage for Rick to make a full recovery,” writes the 29-year old Severson to his young friend. “The courage it will take to pull through all of this will far surpass that needed to take off on any wave.”

A quick scan of Surfer’s contents pages from 1961-63 show no break in the Murphy strips over a span of 14 issues. Prior to the accident, Griffin had apparently stockpiled at least one Murphy. The two-page cartoon, entitled “Murphy’s Adventure in Down Underland,” shows Murphy reading the “Down Under” section of Surfer, hopping a freighter and working off his passage as coal stoker. A get-well letter to Griffin from Severson dated November 13, 1963, confirms he’s holding the strip for publication.

Twenty-eight years later, Griffin would contribute an illustration to San Francisco’s The City of an artist, presumably a grown-up Murphy, on his knees about to enter the gates of heaven. Two weeks after the piece ran, Griffin would be dead of a motorcycle accident suffered while speeding his Harley Heritage Softail down a narrow country road outside of Petaluma, California. He was 47.

*

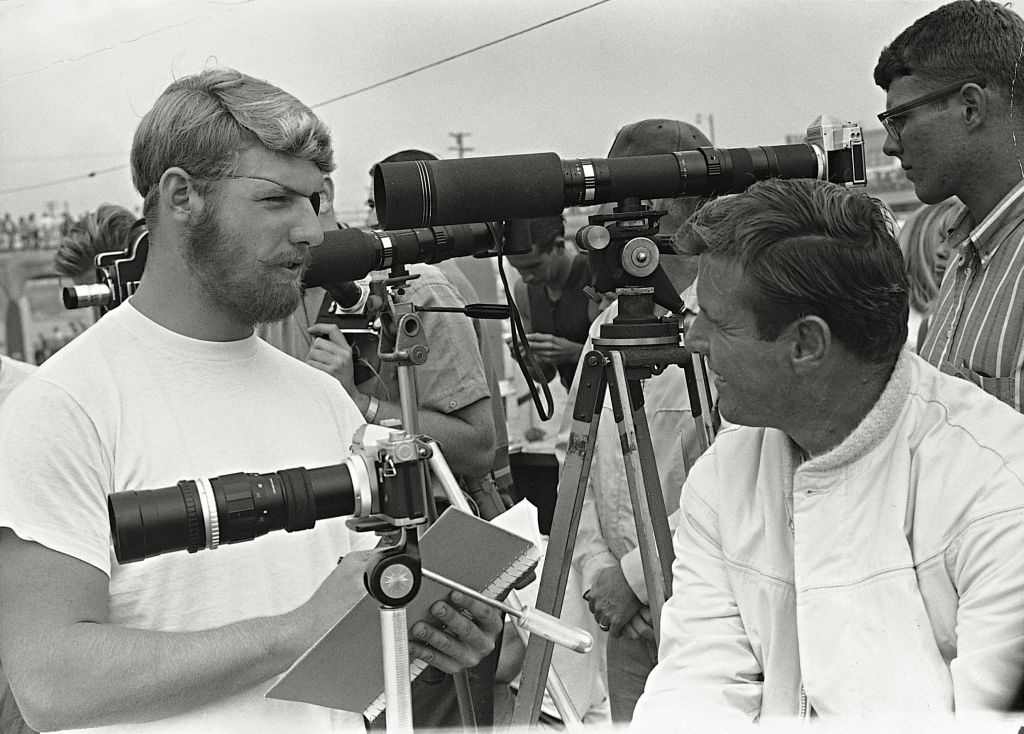

“I noticed Rick Griffin was wearing a patch over one eye and had a beard in the photo on page three of the April-May issue. Has he turned into a Bohemian or Beatnik?”

A Murphy fan, Laguna Beach, California

As early as 1963, Griffin, at age 19, was already a cultural surf star. His Murphy comic strips, which debuted in the second issue of Surfer in early 1961, had proven wildly popular among the magazine’s 50,000 avid subscribers. As John Severson’s teenage protégé, Griffin’s career arc was steep and seemingly effortless. A certain degree of rarified notoriety followed.

Griffin’s cartoons more or less defined Surfer’s early look and, to a large extent, its voice. Whereas John Severson’s characters were whimsical, mute ciphers, Murphy spoke directly to the young, mostly male audience of the era in a polite but defiantly cheeky tone. Murphy hit his apogee as a surfing cultural hero early on when he snagged the cover shot of the August/September 1962 issue.

With a shock of shaggy bleached hair, perpetually cockeyed grin, and size 14 prehensile feet (always bare), Murphy became an overnight sensation. The early strips, drawn when Griffin was still a sophomore at Palos Verdes High, were crude but strongly rendered. They had a ramshackle “Our Gang” charm to them, complete with a “club howse” and a lizard mascot. The language was gee-whiz exuberant: “neat-o,” “really nifty,” and “huzzawhewy!” It was also Boy’s Life maudlin at times.

But in many respects, Murphy was the teenage Griffin who grew up hopelessly middle class and affected a rather stay-pressed, fresh-scrubbed approximation of a surfer while in high school.

“I think that the early Griffin epitomized the naive stoke of the 60s, the sense of the discovery in the first hula-hoop explosion of the sport,” says Pezman, who captained Surfer as editor and publisher from 1971 to 1991. “He took things like, ‘Murphy versus the Marines’—all the cute, naive underpinnings of what later would become this intensely rebellious thing. At the time, it was an act that the general audience of our world didn’t understand. But surfers regaled in the fact that they were misunderstood.”

Rick was tapped to be Surfer’s staff cartoonist in late 1960 after Severson met Griffin while screening his film Surf Fever at Torrance High. John Severson, who at the time was still primarily a filmmaker, had noted Rick’s shop posters for Greg Noll and was suitably impressed with the 16-year-old’s precocious grasp of line and rhythm.

Over the next two years, Griffin produced an affluence of illustrations for the fledgling surf magazine. Severson, an art teacher turned publisher who was 10 years Rick’s senior, served as employer, friend, mentor, agent, and erstwhile hero. Rick, whose classic surfer boy good looks embodied the California ideal, was vetted as Surfer’s unofficial mascot. Readers wrote in each issue to congratulate Griffin or debate the finer points of Murphy’s performance. Severson spun off Murphy mags, decals, t-shirts, and beer stains.

After graduating from Palos Verdes High in June of 1962, Griffin devoted himself full time to surfing, drawing for Surfer, and partying. By the early 1960s, L.A.’s South Bay had suddenly become the center of the cool universe as the first wave of post-WWII boomer kids reached adolescence. Teenagers, flush with disposable cash, drove a huge youth market of clothes, cars, and music. Mainstream interest in surfing, as a sport and a pose, skyrocketed. Rick suddenly found himself at the eye of a cultural hurricane.

Surf music, a danceable, reverb-heavy instrumental rock that evoked the surging rush and exoticism of surfing, had seemingly sprung up overnight. Dick Dale, playing a deafening “wet” version of the traditional Greek standard “Miserlou” was drawing capacity crowds of 4,000 or more at the Rendezvous Ballroom on Balboa Peninsula. A Redondo Beach garage band, The Belairs, had scored a runaway local hit with “Mr. Moto” the previous summer and became the first music group to marquee themselves exclusively as a “surf band.”

Paul Johnson, one of the founding members of The Belairs, recalls that nobody saw it coming: “What made it exciting was that it was larger than all of us,” says Johnson, who went on to become Griffin’s lifelong friend and spiritual copilot through a later Christian conversion. “It was one of those serendipitous things where you get caught up in this thing and you’re just on for the ride. We rented the Hermosa Biltmore and had to turn people away after we got 1,500 kids in there, all slapping their huaraches on the floor. The noise was deafening. That summer was an explosion.”

Randy Nauert, Rick’s high school surf buddy and best friend, was a guitarist who had played bass with The Belairs and later joined The Challengers surf band in 1962. He invited Rick to several of their local gigs. Rick, who loved music but lacked talent, was irresistibly drawn to the growing surf music scene. He envied Randy the immediate feedback, the instant adulation, and most of all, the girls.

“Rick was always a frustrated rock star,” says Nauert, who got Rick surfing in the ninth grade and originally introduced Griffin to John Severson. “He’d work these all-nighters in a little room listening to music with nobody there. Then his stuff would come out and nobody would recognize him. Whereas for us musicians, we’d play this poetry and music and rhythm all together with all of the hormones of a generation raging through the audience.”

Although the Murphy comics were still in demand, by the end of 1963, Rick was approaching burnout. Having little life experience to draw on, Griffin had quickly run out of plotlines and had to be spoon-fed story ideas from Severson. Still living at home and unable to get into a four-year college because of his abysmal grades, Griffin spent a pointless semester at Harbor Community College in San Pedro taking bonehead prerequisites. He’d begun dating a beautiful Mexican-American girl named Elia but outside of his bi-monthly Murphy strip, he seemed to have no interest in advancing his career or himself.

Conditions at home had reached a breaking point as well. Rick’s parents, Jackie and Jim Griffin, were authoritarian and obsessively status quo. And while they approved of Rick’s prestige as a magazine illustrator, they frowned heavily on Rick’s late-night partying and general lack of direction. House rules were strictly enforced and relations, especially between Rick and Jackie, had grown increasingly rancorous.

Griffin, who had once run away and hid out in a cave above Paddleboard Cove after his parents had grounded him for bad grades, decided to quietly slip away. Australia seemed like a likely refuge. His plan, which may or may not have included a high school chum named Tom, was to book a working passage on a southbound freighter out of San Francisco. Taking nothing but his sketch box, Griffin stuck out his thumb and headed north up PCH.

Details from the actual accident are sketchy but, somewhere outside the sleepy farm town of King City, Rick was reputably thrown from a speeding vehicle onto the highway. He skidded on the left side of his face for some distance, mangling his fine Anglo Saxon features. He later recalled touching his eyeball dangling on his face before falling into coma. The driver, if there was one, apparently fled the scene.

Rick was rushed to Mee Memorial Hospital in King City, where doctors, assuming that Rick was likely to die, performed a cursory patch job. Rick later told Gordon McClelland, his surf buddy and one-time art agent, that he had seen rapturous surreal visions of Christ while in the coma.

While Rick’s young, surf toughened body had suffered mostly superficial bruises and scrapes, the left side of his face had been profoundly disfigured. A crushed jaw required reconstruction and doctors removed patches of skin from under his arm to replace portions of his face erased by the asphalt. Nerve damage left three-quarters of his face without feeling, slurring his speech slightly.

“It didn’t look like Rick at all,” recalls Randy, who drove all night to visit Rick in the hospital. “His facial flesh was green and lifeless looking. I had to stare for a long time and even then, it didn’t seem like him. It was him, but, oh, what damage had been done. I was so sad.”

Rick, who had fled the hidebound confines of Palos Verdes to chase the ultimate surfer’s dream, came out of the hospital maimed and reduced to living in a near infantile state of need with his parents again. Griffin became profoundly depressed and gained weight.

Despite two years of painstaking reconstruction, however, he quit the treatments prematurely. The plastic surgeons wouldn’t allow him to surf for fear of ruining their delicate handiwork. And Griffin had grown weary of the slow painful treatments and his mother’s constant nagging to restore his youthful, innocent facade.

The resultant scarring gave his face an off-balance aspect. A missing lower eyelid left his eye perpetually open, even when he slept. The overall effect was like looking at a baleful paisley teardrop—compelling and often unnerving. Randy tells of children recoiling in horror upon seeing him without his eye patch.

In later years, Griffin would learn to use this searing Rasputin stare to great effect. People meeting Rick for the first time spoke of his quiet intensity and charismatic aspect. More often than not, however, friends say he was just being shy.

“After a while, he began to realize the effect it had on people and he played it to his advantage,” says Pezman. “He would confront you with it, watch you squirm. It wasn’t like he was horribly ugly. It was almost like a Prussian saber scar. It gave him an aura, and I suppose it drove him.”

*

“The day I met the Pump House Gang, a group of them had just been thrown out of ‘Tom Coman’s garage,’ as it was known. The next summer, they moved up from the garage life to a group of apartments near the beach, a complex they named ‘La Colonia Tijuana.’ But this time some were shifting from the surfing life to the advanced guard of something else—the psychedelic head world of California. That is another story.”

Tom Wolfe, The Pump House Gang, 1968

The frontispiece of Rick’s 1964 Surfertoons depicts a cast picture of at least 50 historical pop icons that include Superman, Frankenstein, the Beatles, pirates, Nero, Hitler, Sherlock Holmes, beatniks, Davy Crockett, scuba divers, Dracula, varsity jocks, a medieval axman, Old West desperados, Robin Hood, and even a subliminal flash of boob. Griffin drew himself into the mix sporting a rakish Van Dyke beard and eye patch while brandishing a giant steel-nibbed artist’s pen like a jousting lance. What’s interesting is this eclectic assemblage predates the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s cover—which did essentially the same thing in photo-collage—by two years.

Griffin dedicates his 46-page book to Mad magazine’s Jack Davis, Harvey Kurtzman, and Will Elder. “The three greatest (sic) satirists of our time.”

Griffin’s art had evolved remarkably in the six months since the accident. Unable to surf and confined to his parents’ house, Griffin poured his energy into regaining control over his life. His rendering, which could be slapdash at times, became dense and authoritative. Murphy had chunked up as well, leading one reader to suggest a weight-loss program. By late 1964, Griffin had adopted a raucous but ornate Wild West style that defied the viewer to catch all the subliminal characters and in-jokes.

“You can watch the whole thing start to change,” says his art-school buddy Boyd Elder, himself an illustrator who went on to create album cover art for the Eagles and other 70s rock bands. “At that period of time, 1963 to 1964, it was kind of crude. All of a sudden, almost out of nowhere, he starts to refine his characters. He develops this remarkable style.”

John Severson had long encouraged Rick to polish his craft by attending art college. Rick, after weighing the options, found it preferable to working a day job at nearby TRW or Northrop. Despite his dismal grades, his art scholarship opened the door to nearby Chouinard Art Institute in downtown Los Angeles. His choice of school was based mostly on Chouinard’s relaxed dress code allowing beards and sandals. At the time, Chouinard (later Cal Arts) was the hub of a thriving art enclave that had grown up next to the Los Angeles entertainment and garment industries. Two downtown schools—Otis Art Institute and Chouinard Art Institute—anchored a small village of artists and artisans living in seedy boho splendor in a genteel Victorian neighborhood (since bulldozed) that had been severed by the Ventura Freeway in the 1940s. Of the two, Chouinard, founded in 1921, was considered the more avant-garde.

At school, Rick met Ida Pfeferle, a beautiful 19-year-old Bay area girl studying historical fashion. Her dream was to do costume design for big Hollywood musicals like My Fair Lady. She was first attracted to Rick’s tanned, teddy-bear persona and the captain’s hat he wore. “My dad was in the Navy and I always lived by the ocean, so I thought, ‘Well, this guy likes boats, so he’s gotta be cool.’”

Born in London to an American dad and British mom, Ida was much worldlier than Rick, whose genteel middle-class upbringing Ida describes as “really upright—something out of Leave it to Beaver.” Before she was 10, she had traveled through Europe and had lived in Morocco for three years. With elfin good looks and long blonde hair, Ida embodied Rick’s idealized archetype of a surfer girl, even though Ida had never surfed.

Although neither was really what the other imagined, they connected on a quaint, endearing level. “We had everything in common at the time,” recalls Ida. “I collected comic books. He collected comic books. We both liked to go into record stores and look at album covers. We both loved the ocean. He never took anything too seriously—a roguish, gentle, big guy.”

Over their tumultuous 27-year relationship—one that ended suddenly in 1991 on an anguished and unfinished minor chord—Ida became in turns his girlfriend, wife, muse, acid guide, keeper, model, and mother of four of his children. Rick would later immortalize her as a sultry guitar-strumming Beat Madonna in the Griffin-Stoner adventures. “They were soul mates, even if Dad didn’t know it,” says daughter Flaven.

Rick’s fellow artist and Chouinard teacher, Rick Timberlake, had leased part of a disused tortilla factory on Temple Street and a small but vibrant bohemian scene soon aggregated around a slew of spacious old Victorians and warehouses transformed into ad-hoc artist lofts. Weekend-long Dionysian wine rites and art shows soon became the norm. Rick and his art school buddies reveled in their newfound liberation. Rick, who had started smoking pot in the 12th grade, was soon experimenting with LSD and other psychedelics filtering down Highway 101 from the fomenting counterculture brewing up in San Francisco.

By the beginning of the second term, Rick and Ida moved into the tortilla factory. Ida recalls a charming, eclectic neighborhood that reminded her of a scaled down Greenwich Village. One of its denizens, she says, inspired a surf-cult icon.

“Above where we lived there was this little Mexican kid,” recalls Ida. “He was five years old and he loved Rick. He would come up and hang out for hours watching Rick draw. So Rick started putting him in Griffin-Stoner adventures. That’s why you see the little ‘Chine Boy’ pop up in every cartoon after that.”

By the summer of 1965, the Sunset Strip club scene was on high simmer. Back in the medieval days of rock, it was possible to see many now-legendary artists—The Byrds. Buffalo Springfield, Joni Mitchell, The Doors—for a two-drink minimum at small clubs like Gazzari’s or the Whisky a Go-Go. The British invasion had hit the year before and the hottest English groups—the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, The Who, and others—were funneling through the L.A. record companies weekly. Chouinard was only minutes away from Hollywood and the easy interplay between rock music and graphic arts would lead to the explosion of late 60s album art and later the MTV revolution. Griffin bridged three powerful cultures—rock, art, and surfing—effortlessly.

“The girlfriends would go out with the rock stars and then they would bring them to the gallery openings to flaunt them,” remembers John Van Hamersveld, a one time Surfer art director who designed the heraldic, day-glo Endless Summer poster in 1964 while a student at Otis Art Institute. “So then, the rock stars would take us to their kind of parties. The thing that both Rick and I had going for us was that we were surf beatniks. We were from a mystical world—the ocean—and we had stories about these things that were quite amazing.”

In mid-1965, having moved on from his adolescent surf persona, Griffin decided to kill off Murphy in spectacular melodramatic fashion. In a two-part episode entitled “Murphy Hits the Skids,” a shabby, careworn Murphy loses his job and is reduced to selling pencils on Skid Row. He’s beat up by thugs and left (tellingly) with a left black eye. In despair, he attempts suicide. Although he’s redeemed in the following issue, Murphy was mothballed indefinitely.

In the same issue (May 1965), however, Griffin in cartoon form takes over. Paired with Surfer’s new staff photographer Ron Stoner as a sort of surfing Martin and Lewis, the Griffin-Stoner adventures kicked off for a 12-issue run spanning two years.

The debut adventure opens with a mock memo from then editor Pat McNulty for the duo to drive up to San Francisco and photo-illustrate Fort Point’s mystery left breaking under the Golden Gate Bridge. Stoner is played as a gee-whiz ingénue, while Griffin is the one-eyed, skirt-chasing rogue, forever scamming McNulty out of more money, which he invariably squanders on wine and Watusi lessons.

In a meandering plot arc—told through a flurry of urgent telegrams, postcards, and chatty journal entries—the disorderly duo get into scrapes all the way up the coast. Along the way, they hire a crane to surf Big Sur, have to be rescued from hungry sharks atop Pinnacle Rock at Steamer Lane, and end up leading a North Beach protest march. They finally get the shot (by buying it from another photographer), but only after leaving a trail of frivolous expenses and steam coming out of McNulty’s ears.

Judging from the letters column in the following issue, Surfer’s readers synched in quickly. Dogtown’s Skip Engblom recalls devouring the Griffin-Stoner adventures as a young surfer growing up in Venice, California: “I remember saying, ‘Man, I really want to go with Griffin and Stoner on one of these trips.’ There was this real goopy sense of fun with it. But, at the same time, Griffin was giving you under-the-table information you really wouldn’t pick up in the newspaper.”

The stories were co-written by John Severson and then-editor Pat McNulty in a madcap, often hopelessly hokey sitcom style. But in the era of zany costume farces like The Great Race and Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, they brought an edge of pop credibility to the magazine. They also brought Griffin out of his emotional keep. Griffin’s cartoon persona, hipster cool and confident, traveled to all the exotic surfing ports-of-call that the shy-damaged art student couldn’t.

“If you track his first Griffin-Stoner adventure to his more mature ones, you can see incredible growth,” observes Severson. “You could give Rick a simple idea like, ‘Natchez to Mobile (With Griffin and Stoner)’ and ‘boom!’ He’s all with it, with a two-foot-wide drawing of a Mississippi paddlewheeler with Griffin riding a wave off the back of it. They are wonderful, wonderful things. By that time, he had synced his imagination with his pen and he could really go.”

Meanwhile, Chouinard, despite the extracurricular attractions, was proving a well-known drag. At a time when abstract expressionism absolutely dominated art academia, anything remotely representational was considered highly démodé. “If you even had two lines that converged, suggesting perspective, it was a no-no,” recalls Rick’s friend and Zap Comix cohort Robert Williams. “I had one hell of a time. It was a horrifying experience because you had the talent, the ability, and this urge, and it was absolutely stifled.”

Bored and artistically crabbed, Rick would cut class to go skateboarding at a nearby supermarket parking lot. The last straw came when Rick was told by a cigar-smoking pedantic: “You know, son, you can’t make art with a Rapidograph.”

Griffin dropped out after his first year and never returned.

Griffin’s 1965 output, however, was striking in its depth and volume. In a one-year span he produced comics and spot drawings not only for Surfer, but also moonlighted for Skateboarder, Surf Toons, Drag Cartoons, and Big Daddy Roth hotrod cartoons. He drew ads and album art for The Challengers. Finally, exposing Griffin’s exhibitionist streak, Griffin played preening racecar poser “Griff Murphy” in “The Big Blow” photo-toon.

Griffin’s covert need for a live audience soon translated into the Jook Savages, a ragtag jug band cum performance-art troupe made up mostly of Griffin’s art school posse. Rick played blues on a one-string zither, an arcane homemade instrument played with a beer bottle and a stick.

“The band was loosely strung together but, nonetheless, it had a real rustic charm about it,” recalled Griffin. “At that time folk music was in full bloom and the jug band was a perfect medium of expression. We were a self-styled tribe.”

Sometime that Christmas season, Ida walked into their loft and told a guitar-strumming Griffin she was pregnant with his child.

Rick, who had no interest in becoming a father or a husband, kept strumming and bluntly told Ida to get an abortion. Ida was upset but quickly came to a decision. Without giving Rick an ultimatum, she decided to keep the baby. She packed up and left to go live near her family in the Bay area, renting a room with her sister near Haight-Ashbury.

Rick, suddenly alone, pondered his future for the moment then went to the Acid Test.

In early February 1966, the Jooks had been invited to play at one of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters’ celebrated Acid Tests—ecstatic communal dance rites that simulated the LSD experience by mixing kaleidoscopic light and movie projections, hallucinatory strobes, free-association rap, and a sonic wall of throbbing improvisational rock. And for those who wanted the real thing, a dose of notoriously potent Owsley Blue was freely available via a cup of specially spiked Kool-Aid. LSD would still be legal for another eight months.

The Tests were held in the Compton Youth Opportunities Center, a cavernous warehouse near Watts. It was a bold, even foolish move. Only six months before Watts had erupted in fiery race riots that left 34 people dead. Inside, the Merry Pranksters and the Grateful Dead set up and wailed all night like day-glo banshees. Rick and his buddy Boyd hooked down two cupfuls each and wailed right along with them.

Jerry Garcia, reflecting at Rick’s wake in August 1991, recalled first meeting the 21-year-old Rick at the Acid Test. “I never realized that it was the same Rick who had done Murphy,” recalled Garcia, himself a voracious comic book collector from his teens. “I’d seen his Zap stuff and ‘Tales from the Tube,’ but I never put the two together. Later on, I could relate to his art because it was very similar to my own psychedelic experiences. I’d look at those and I’d say ‘Right-on, Rick—you killed it.’”

An account of the Watts Acid Test would later be immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test. “It was pretty impressionable stuff,” recalled Rick. “It was just total, beautiful pandemonium inside that hut.”

Afterward. Rick, now an ecstatic acid convert, tried unsuccessfully to get his parents to turn on with him. Failing that, he turned his attentions on the surf world.

Starting with “Le Adventure Surf Francais” in March 1966, Griffin began slyly infiltrating the Griffin-Stoner adventures with then-cryptic drug symbology. The ZigZag rolling-papers man shows up in the first panel and by the last scene Griffin is merrily puffing away on a hookah aboard the fantail of a sheik’s yacht. Finding the pot references in Griffin’s cartoons soon became a point of honor among a small but growing number of head surfers.

“He was the Trojan Horse,” says Drew Kampion, Surfer’s editor from 1968 to 1972. “He made that underground connection in a more public way than any other surfer did.”

Emboldened, Griffin threw increasing numbers of psychedelic references into each succeeding issue. By “Guess Who’s Minding the Store” (Sept 1966) he’d transformed the Surfer offices into a hip disco complete with day-glo mandalas and caged go-go girls. The discerning eye will note the marijuana and magic mushrooms growing in the planter boxes.

“A lot of this stuff went by unnoticed for a while,” said Griffin. “But it was pointed out to the editors of Surfer by some of their more major and straighter advertisers that I was putting all these ‘dangerous’ references in my cartoons. So, they told Surfer if you don’t get this guy to straighten out, we’re going to pull our ads. Hobie specifically put the pressure on Surfer to get me to clean up my act.”

Relations between Severson and Griffin strained considerably. Griffin felt he was fast outgrowing the magazine, and Severson, who by mid-1966 was playing golf with Orange County Republicans, was incensed that his one-time prodigy was thoughtlessly bringing the surf establishment down on him. “I didn’t like it that Rick slipped those things in on us,” said Severson, “so I slipped one or two back at him and he stopped doing it. No, that’s wrong, he didn’t stop doing it. If you look close in the Mexico one (‘What Happened to Griffin?’ January 1967) you see they’re carrying bales of weed on those jungle rafts.”

Severson ran afoul of Griffin’s messianic eye when he subtly altered Rick’s work to skew a couple of the drug references (of which Severson had little real understanding). The changes were undetectable to all but Griffin, but to Rick it was an act of betrayal by his one-time hero. “I started getting real pissed off about this. My heart was less and less in it.”

Early that summer, while on a pot-buying sortie to a friend’s to house in L.A., Griffin spied an ornate, old-time poster drawn the previous summer. It advertised a show up in Virginia City, Nevada, by The Charlatans, San Francisco’s original acid-rock band. The Charlatans—who wore eclectic thrift-store fandangle and played a rambling electrified folk-rock—freely encouraged their fans to turn on with them. For three summers, 1965 through 1967, they appeared at the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, an Old West ghost town turned tourist trap. It became a magnet for the embryonic head culture now well underway in San Francisco. “What the Cavern Club was to the Beatles, the Red Dog was to the psychedelic music scene,” wrote one rock historian.

Griffin was mesmerized. “It was crudely but beautifully drawn…the band members were pictured as these sort of Edwardian, art nouveau, Wild West dandies all decked out in all this finery of yesteryear. It had all these overtones of the new music and rock-and-roll and the art counterculture that was emerging in the Bay area. It was just, I think, the coolest image a band could ever have.”

Less than a week later, Griffin was up in Virginia City where he turned on and met the band. “That trip to Virginia City was the last straw,” said Griffin. “I realized that I was going to become part of this.”

*

“San Francisco is 49 square miles surrounded entirely by reality.”

Paul Kanter, Guitarist, Jefferson Airplane

Flaven Heather Highland Griffin was born in July 1966 at UCSF Hospital, making her one of the original Haight-Ashbury love children.

Flaven’s reluctant father, meanwhile, had sold his L.A. studio and slipped across the border on extended surfari to San Blas, Mexico. He’d been up to San Francisco briefly in June to look in on Ida, but had also been checking out the extraordinary new rock-concert posters being drawn by Wes Wilson and Ida’s neighbors, Stanley “Mouse” Miller and Alton Kelly. Since leaving L.A., Ida had been sending Rick handbills from recent shows to clue him in on the blossoming psychedelic music scene.

Shortly after his arrival in Mazatlan, Rick wrote Ida, blustering about his tortuous journey south braving desperados, alligators, and man-eating potholes to catch a decent wave. To Rick’s storybook sense of adventure, Mexico seemed an exotic third-world frontier teaming with cinematic danger and intrigue. Ida had a chuckle and got out her suitcase.

“I laughed because I had traveled a lot as a kid and I knew it wasn’t a big deal to go down to Mexico,” says Ida. “So I just got on a bus in Tijuana with Flaven, who was six weeks old, and my friends Gus and Mary, and we all went down to Mazatlan to see Rick. Rick didn’t know we were coming. He tried not to act surprised when we showed up on the beach out of nowhere.”

The new family set up under a beach palapa at San Blas and quietly worked it out. For the next two months, they lived an idyllic existence: surfing, sleeping in hammocks under the stars, eating fish tacos, and sipping fresh coconut juice from the husk. Rick’s surfing had tapered off to almost nothing while he was at Chouinard and he was fast rediscovering the stoke. While making no promises, he also made his first tentative steps toward fatherhood.

One day on a foray up into the nearby Sierra Madre mountains, Rick and Ida encountered the reclusive Huichol Indians, a shamanistic tribe renowned for their vibrant yarn paintings and bead design inspired by peyote-induced visions. The Huichol and their sacred art fascinated Rick and one can see wizened mescaleros begin to pop up as recurring motifs in the Griffin-Stoner adventures soon afterward.

Rick and Ida returned to California mid-November where Rick had been invited, along with the rest of the Jook Savages, to stage an art and music show commemorating the one-year anniversary of the Psychedelic Shop on Haight Street. The Psychedelic Shop, arguably the world’s first head shop, acted as switchboard and supply depot for the San Francisco under-ground. Rick was commissioned to draw the poster.

Inspired by the Charlatan’s Red Dog Saloon poster (since dubbed “The Seed”), Griffin quickly generated his own, more finely rendered collage that bent and contorted the type into eccentric, barely legible forms that supposedly re-created the acid experience. At the printers, Griffin ran into the folks from the underground newspaper The Oracle (later called “the Rosetta Stone of the Hippies”), and the depth of Griffin’s painstaking draftsmanship blew them away.

Rick was asked immediately to contribute art to The Oracle and other head “happenings.” “They told me, ‘We’re having this big event in the park a week from now. It’s called The Gathering of the Tribes.’ They called it the ‘Human Be-In.’ That was the first of a series of events like this that happened all over the country, which ultimately led to Woodstock.”

Rick’s poster, which heralded the coming age of Aquarius, pictured an Old West Indian on horseback cradling a guitar with one arm and holding up his ceremonial blanket with the other.

On January 14, 1967, over 20,000 newly fledged freaks—drawn by radio announcements and Rick’s poster—converged on the Golden Gate Polo Grounds. (“It’s like someone lifted up a giant flat rock and we all crawled out at the same time,” quipped underground FM DJ Tom Donahue.) The joyous all-day event featured Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure, Timothy Leary, and Richard Alpert as the keynote cheerleaders. The Jefferson Airplane played, everybody grooved, and an invitation went out to the youth of America that a new Oz was awaiting them in San Francisco. The Summer of Love was on.

Rock impresario Chet Helms saw Rick’s posters and asked Griffin if he would create poster art for Helms’ weekly dance concerts at the Avalon Ballroom. The deal was $100 per poster and the artist kept the original. Soon after, first-time publisher Jann Wenner asked Griffin to do the cover logo for a new music magazine to be called Rolling Stone. Griffin made $150. Griffin, who embodied a cross between Siddhartha and Forrest Gump, was nonplussed about his success.

“I just sort of stumbled into the Bay area and was drawn right into this whole scene,” admitted Griffin. “Actually it happened just about like everything else that’s happened to me in my life.”

Starting with a Michelangelo-inspired (actually, ripped-off) photo-collage for Big Brother and the Holding Company (featuring a then-unknown Janis Joplin), Griffin went on, in just under two years, to create a streak of mind-bending psychedelic art for the elite of 60s rock. A short list of the bands includes Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix, Iron Butterfly, The Doors, Canned Heat, and Santana.

Alton Kelly, one of the “Big Five” of San Francisco poster art (together with Rick, Stanley Mouse, Victor Moscoso, and Wes Wilson) likes to compare the friendly but keen rivalry between the poster artists as the same creative prod that drove Toulouse-Lautrec and the other artists of the La Belle Epoque.

“In the very beginning with the five of us, there was a funny kind of competition,” said Kelly. “Everybody knew each other. We would go out on the street and look for Wes’ work, and look for Victor’s work, and look for Rick’s work. And it would be, ‘Oh my god, look what he’s done.’ It was so great because then we’d have to go back and really do something good.”

In July of 1967, during the height of the Summer of Love, the Big Five staged a showing of psychedelic poster art at the Moore Gallery downtown. Jokingly called the “Joint Show” (Rick drew a poster of fat, double-enders protruding from a cigarette pack), the event drew thousands on opening night. Janis Joplin and Big Brother jammed all night on the artists’ behalf. Life Magazine covered the opening and Rick was featured in the September issue as one of the premier artists of “The Great Poster Wave” sweeping the country. Rick’s star arced higher, even if the pay didn’t.

Griffin turned in his last-ever Griffin-Stoner adventure, “Deep in the Heart of Texas with Griffin and Stoner,” horribly past deadline in late June 1967. Predictably, it had no photos, surf or otherwise. But it did have a now classic skull and roses Grateful Dead poster (lifted from a September 1966 Avalon Ballroom concert) drawn by fellow poster artist Stanley Mouse. It also had Rick playing the one-string zither with the Jook Savages against a vibrating op-art backdrop.

While there were no overt drug references, marooning Griffin in the middle of Texas was perhaps an indicator that both Severson and Griffin had run out of interest in continuing their professional, and even personal, relationship. Severson, who knew Griffin’s style intimately, felt that lately Griffin had been phoning in his Surfer art, not taking the time to properly finish them off.

“He just wasn’t interested anymore, and I wasn’t too thrilled with the last couple things he did,” says Severson. “He just went off to San Francisco and did his poster thing and we moved on.”

Two issues later, after a six-year run, Griffin’s name, and Griffin, quietly disappeared from the Surfer masthead.

That October, Rick was given the assignment to produce a poster for a Quicksilver Messenger Service show at the Avalon Ballroom. Having run out of time, Griffin hastily concocted a stopgap graphic solution that drew directly from his Murphy cartoon days at Surfer. He composed the poster as a mock comic strip that appeared to have logical comic strip progression. But on closer inspection (often on a street corner telephone pole), the strip transformed into a radiant visual palindrome filled with looking glass puns and quirky non-sequiturs. In the ninth panel, Murphy, wearing baggies and holding his board, pops up apropos of nothing and chirps, “OK Optimo, hoist ’er up.” Suddenly a single forgotten refrain of bitchin’ surf tremolo floated over the Haight.

“The reason I liked creating an art that had the appearance of a comic was because it was a throwback to a period of time when I could care less about the status quo or what was acceptable or not acceptable or valid art,” said Griffin. “It was just pure enjoyment.”

The poster was a huge hit with the heads and his artist peers, who viewed Rick as a kind of boy wonder from the surfing underground. Griffin had stubbed his toe on a wholly new style of non-linear storytelling that revolutionized the comic genre. Robert Crumb, then a struggling illustrator hawking his first issue of Zap Comix from a baby carriage on Haight Street, saw the poster and was over on Griffin’s front porch immediately. He wanted Griffin’s art in the second issue of Zap.

Griffin joined a small but influential crew of disaffected cartoonists who specialized in graphic sex, gory violence, drug humor, scathing socio-sexual satire, anti-establishment messages, eco-awareness, and what one underground comic expert defines as “nasty subversive fun.” Their trailblazing, however, opened the door for the flood of “alternative” comics that fuel a billion-dollar comic publishing industry these days.

The first Zap artists were Crumb, Griffin, S. Clay Wilson, and Victor Moscoso. They were joined a few issues later by Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert Shelton, and Robert Williams. Zap #2, published in 1968 (“Gags, Jokes, Kozmic Trooths”), featured 12 pages of Griffin’s art. He remained with Zap until the mid-1980s.

For the most part, Griffin veered away from overt pornography, although he dabbled occasionally. Griffin’s brief stabs at erotica, however, never expressed the misogynistic angst of Crumb or the twisted low-rent psychosis of S. Clay Wilson. His sexual imagery was more idealized fertility symbols than pornography or sexist satire. His “Oxo” drawing is a seething wet mandala of spurting genitalia, but it’s done with such skill and symmetry it could easily be used as a religious icon, which perhaps it is.

“He lived in his own world, or rather his own mythology,” recalled Crumb shortly after Griffin’s death. “Even when he was a Jesus freak, it was his own crazy romantic version. He’d claim the Bible said the earth was populated with a race of giants. Stuff like that. I think he even found surfing in the Bible. Stuff nobody else ever saw.”

By the end of the summer of 1967, however, the once-vibrant Haight-Ashbury art scene had soured. The Gray Line tour buses were now bringing tourists in to gawk at the hippies and the flood of teenage runaways attracted a food chain of predators like Charles Manson. The once funky artist’s ghetto quickly succumbed to overpopulation, rip-offs, rapists, heroin, and speed epidemics. “The language was love,” writes Hunter S. Thompson, “but the style was paranoia.”

Late in 1968, after consulting the astrological charts, Griffin became convinced that come spring an earthquake of apocalyptic magnitude would cause California to snap off like a hunk of chocolate and fall into the ocean. Believing the end of California was nigh, Rick loaded his art supplies, together with Ida and Flaven, into a VW van and headed east for higher ground shortly after New Year’s 1969. Ida, who was three months pregnant with their second daughter, Adelia, at that time, rolled her eyes but got in. One morning, after a lightning-spiked night camping in Monument Valley, they threw the I Ching and decided to visit their old Chouinard buddy Boyd, now living in El Paso. They camped in a converted water tower for two months, with Rick repainting the kombi’s dashboard a shade of gold over and over until he got it perfect.

In later years, Rick was philosophical about the Haight’s brief renaissance as the Hippie Versailles: “All these things were very short-lived,” he reflected. “They were like the grass in the spring, you know? As soon as the summer sun gets on it and scorches it, it all withers away.”

*

“Surfing is kind of like the Dance of Shiva. Shiva dancing on the dwarf of ignorance…it will always be a way to keep in touch with the Earth and forget about all the bullshit and all the madness of modern life. That’s why I love it so much.”

Rick Griffin, 1989

By 1969, Surfer magazine was for a brief time a cultural flagship, not only for the surf community but the entire American youth revolution. As much as Rolling Stone magazine, it mirrored the values and spiritual yearning of a dysfunctional generation trying to come to grips with the lies and fundamental cruelty underpinning the American Dream.

“There was an underground conspiracy at Surfer to reflect and show its support of and empathy for the peace and freedom side of the surfing thing,” says Pezman. “Surfing was a very avant-garde way to see life at that moment. A lot of people were going off to work and marching off to war and surfers were just going after shortboards and flipping off all those things.”

With the Apocalypse apparently postponed, Griffin was enticed back to California by his old mentor-employer, Severson. By late 1968. John was feeling burnt out and trapped within an upholstered prison of his own making. His life, he wrote, had devolved into, “Golf championships, member-guests, cocktails and cards, birdies and bogies, and unbelievably shallow lives drifting through the whole miserable scene.”

Moreover, Surfer’s readers had passed him by, leaving Severson horribly out of touch with his own audience. He was also at a loss relating to most of his young, turned-on staff. He became alienated and paranoid. “John basically missed the 60s and was trying hard to catch up,” says Drew Kampion.

Apparently at some point, one of his junior staff took John aside and quietly got him stoned. More importantly, perhaps, they got him out of the country club and back surfing again. He renewed his vows. A wholesale conversion followed, and Rick was asked back to the magazine. “One of the first things John realized was that Griffin wasn’t so bad after all,” recalled Rick. “So he contacted me and said ‘Rick, all is forgiven. We want you to just pull out the stops and create something really electric for the magazine.’”

Murphy’s return to Surfer in the May 1969 issue was unheralded and spectacular. Murphy, like Griffin himself, had come back from psychedelic crusades essentially retooled. In an existential tone poem, using the Zap-style of non-linear storytelling, Murphy is reincarnated as a surfing Hopi demi-deity tracking across an arid Dali-esque mindscape filled with cosmic portents and paradisiacal right-handers (Griffin was a regular foot). By the end of the cartoon, a burning-eyed Murphy awakes from a trance spouting an ancient quadrangular riddle: “Arepo the sower, holds the wheels at work.” By now, most of the surfing world had gotten a clue as to where Rick was coming from.

In the wake of rampant beach development and the devastating Santa Barbara oil spill of January 1969, Severson’s dormant environmental conscious had been awakened as well. As his swan song to surfing before selling Surfer and moving to Maui, Severson felt he needed to make one last surf film that reflected surfing’s new role as cosmic teacher.

“I wanted to make a film that would jolt a lot of people awake to what was happening to the ocean and our environment and what was going on,” says Severson. “I didn’t really want to make another film to make another great surf film. I wanted to make a statement.”

Mortgaging his house for seed money, Severson started filming in late 1969 and auspiciously scored epic 15-foot Honolua Bay with Jock Sutherland and Billy Hamilton during the fabled winter swell of ’69.

Rick was brought on board to create a movie poster and to provide an overall graphic look. Griffin’s cartoon imagery and calligraphy is used liberally throughout Pacific Vibrations in powerful, near subliminal blips. One of his first tasks was to help Severson paint an old school bus in psychedelic surf mandalas, à la Ken Kesey’s venerable “Furthur.” Armed with buckets of paint and brushes, Severson, Griffin, art director Hy Moore, and a couple of ends quickly transformed the dowdy little olive-green bus (done to a bubbly raga beat provided by master Ashish Khan) into a lurid, grinning mind-machine dubbed “Motorskill.”

In the Ranch interlude of the movie, Rick is portrayed as a friendly enigmatic—the Jesus-tressed Cosmic Driver who speaks an ornate but unintelligible “Griffinesque.” In Griffin-penned subtitles, he smoothly raps his way past the Hollister gate guard. In the introductory vignette, Griffin swings open the bus door with a witchy zing, beckons come ride, and presumably we all got on.

Along for the ride in early February 1970 were Severson, surfers Angie Reno, Mike Tabling, and Brad McCaul; photographers Brad Barrett and Art Brewer; and yearling editor Drew Kampion. Along the way, they picked up three hitchhiking Valley girls and the whole thing turned into an endearing three-day soul trip that captures that first exuberant rush of adolescent freedom. The Ranch footage paints a heartrending portrait of the last vestiges of the California ideal: sagebrush hills, dirt roads, eucalyptus groves, small, cold, kelpy tubes, crisp offshores, and dusty red sunsets setting in a Western sea.

Rick, who never evolved out of the longboard era, is shown cruising on an anachronistic 9’0″ at Lefts and Rights to the languid martial beat of “Wooden Ships” by Crosby, Stills, and Nash. Rick’s surfing style mirrored his cartoon personas: low and fluid languid hands caressing the wave face. “I was, at that point, back into my surfing career, which had been interrupted for years with all this other stuff,” said Rick. “I hope I never go so long again in my life without riding waves.”

Despite the surf never topping three feet, Severson later wrote that the Ranch sequence came closest to what he was trying to achieve in his movie. During the first year of filming, Severson installed Rick and family (second daughter Adelia was born in July) in a Beach Road house in Capistrano Beach hoping that he would produce a poster in a couple of months. After eight months, Severson demanded Rick show him the painting. Griffin reluctantly agreed.

“Actually there were two poster,” recalls Severson. “He finished the poster and it was fabulous—a great poster. And he said ‘Well, I’ll give it to you tomorrow.’ Then he and a friend got into something, some potion, and he decided overnight that the poster wasn’t what he wanted and he painted it white. I came the next day and the poster was gone—painted white—and he had started over.”

Two months later, however, Severson was presented with a masterpiece. The second Pacific Vibrations poster, rendered in rich orange and aquamarine tones, became an instant icon. Griffin had fused his psychedelic poster art and surf cartooning into a deep sensual tableau that heaved off-page in salty wet surrealism. The beautifully drawn tube becomes a literal womb for a growing fetus while the sky convulses in an aurora of sperm-like droplets.

The movie itself opened to lukewarm reviews and ultimately flopped at the box office. After brokering a deal with Hollywood (“I had delusions of grandeur,” says Severson), the movie fell into a miasma of compromise. In turns profound then pretentious, funny then didactic, Pacific Vibrations neither drew in the coveted mainstream audience nor totally stoked out the surf brethren.

Upon release in late 1970, American International Pictures gave it only superficial distribution and then canned it within a month. The movie has remained in limbo for over 30 years due to hassles over ownership and music copyrights.

Still, if one gets their hands on a bootleg video version, and turns the sound down on Jock Sutherland’s scripted cosmic musings, the film holds up remarkably well as pure eye candy and a quirky time capsule of West Coast pop history

A few months after Pacific Vibrations’ premiere, Severson sold Surfer at age 36 and retired to Maui to paint, surf, and grow citrus. Drew Kampion quit and Steve Pezman was tapped as the new editor-publisher.

Rick’s relationship with Surfer sputtered off and on for the next couple of years as he became a born-again Christian and began illustrating the Book of John for the Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa. Murphy, predictably, became a bright-eyed, scripture-spouting zealot, strangely devoid of personality.

“We always tried to have Rick reincarnate Murphy and bring him back so we could do the feel-good neat deal again,” recalls Pezman. “But he never would bring him back. Rick was never going to be the same and Murphy was never the same again. Murphy had found God. Murphy had gotten stoned. Murphy had taken acid. Murphy had a car wreck. Murphy was not Murphy anymore.”

Griffin, at first pass, seems an unlikely avatar of the 60s. Though often drawn as a barefoot wandering mystic, at heart he was a card-carrying SoCal man: all surfboards, hotrods, Ray-Bans, drive-in cool—a modern American primitive. Rick in his day was the ultimate insider: young male, middle-class, Southern Californian, a surfer. He could have easily disappeared into the soul-chomping shark’s maw of American materialist mediocrity. Instead, through dumb luck and divine timing, he became the eccentric UV-joint coupling a slew of disparate youth cults together. He translated their arcane jargon, melded them together through his own experience, and turned on the world.

And along the way, surfing.

“Griffin was the cornerstone of a whole movement that was really a way of looking at life and what’s worth doing in life,” says Pezman. “Surfers think riding a wave is really worth living life for. Rick, for a while, was the most visual dream-maker of that message.”

*

Postscript: In the fall of 1976, after traveling to Europe for an art show in London, Griffin and Gordon McClelland bought an old Morris Minor and drifted over to France where they camped at Seignosse. Griffin finally made it to the Biarritz train station so that he could say he actually lived one of his cartoon adventures. Gordon says they drove to Spain soon after, where they drank tequila with Basque terrorists and scored 12-foot Mundaka with only three people out. But that’s another story…

Photograph by Henry Diltz.

[Feature Image: Rick’s 19th birthday, June 18, 1963. John Severson recalls visiting a 17-year-old Rick at Griffin’s parents’ Palos Verdes tract home: “His room was just end to end posters, ceiling to floor. He had everything imaginable. You went through this straight house with the straight couch and the lamps sitting up straight and the cat sleeping in the corner. Then you went through the door to Rick’s room and it was like: ‘Whack!’” Photograph courtesy of Ida Griffin.]

Special thanks to: Randy Nauert, Denis Wheary, Gordon McClelland, John Grady, and Gary Burdon.