It’s a Saturday morning in La Jolla, California, 1982. Sitting on the counter at Mitch’s Surf Shop is a stack of surf magazines, which had appeared overnight. Nobody at the shop knows where they came from.

They aren’t copies of Surfer, nor Surfing. This magazine features no Americans and no surf contests. Instead, it’s filled with wild-eyed men driving through frontier landscapes with surfboards on the roof, headed for mystic surftopias named Eagle Island, Coffee Rock, and Camp of the Moon. For the teenage surf urchin who walks into Mitch’s that morning and picks up a copy, it feels like an exotic treasure sparkling like an opal as he flicks the pages, a riot of new-wave color and shape. His mind races.

This magazine, it turns out, is from a parallel surfing universe: Australia. And it has landed on the counter at Mitch’s thanks to the efforts of a Californian named Blue Trimarchi, who’d himself stumbled across it on a trip to its native land. Spellbound, he’d begun importing each new issue at a modest consignment.

The publication’s title? Surfing World.

Though it had been in print since the early 1960s, on this Saturday morning Surfing World is in the midst of a golden era, being run from a spare bedroom on Sydney’s Northern Beaches by two surfers. The duo would produce the magazine for 25 years, creating a surfing canon that marked the high-water line for not only their own title, but, arguably, for surf magazines entirely.

Those two surfers turning its gears? Bruce Channon and Hugh McLeod. Bruce and Hugh. Hugh and Bruce.

•

As surfing swept across Australia in the late 1950s and early 60s, Bob Evans, a former lingerie salesman, saw opportunity everywhere he looked. In a non-exhaustive list, Evans became a filmmaker, publisher, editor, columnist, agent, impresario, promoter, administrator, mover, shaker, and “sunset connoisseur”—all of these roles performed in a suit and tie.

First published in 1962, Surfing World appeared to be just one element of Evans’ vertical takeover of the country’s burgeoning surf industry, though it quickly functioned to inspire Australia’s surfing identity of the era. For example, the inaugural issue featured a road-trip story titled “Discovery in the North,” put together after Evans was tipped off by his brother about a right-hand pointbreak while fishing for snapper. The “discovery” was Angourie. In those years, each issue would reveal a new Angourie, empty points lined with pandanus trees seemingly dotted everywhere along the coast.

In actuality, the magazine was part of a much larger plan. Evans had been in Hawaii in 1963 when Midget Farrelly won the Makaha Invitational, and he’d closed out his report by writing, “I am certain Australia could present a world championship that would be second to none. It’s just a thought at the moment, but I have no doubt about its ultimate success.” Evans, of course, was already working on it. Just over a year later, the first World Surfing Championships were held at Manly Beach. Midget won there, too, fulfilling Evans’ prophecy.

Amongst the crowd that day at Manly was a 13-year-old who’d surfed in the juniors division, and who at the event came to an immediate and blinding realization: “Surfing people are the people to be around. [Surfing’s] all that matters.”

Bruce Channon grew up at Mona Vale, a quiet kid from a quiet beach. After finishing school, he began working at Farrelly Surfboards as a finish coater before eventually working as a glasser for Geoff McCoy. Indeed, Bruce came up among surfing greats and could hold his own at work and in the water, though his demeanor made him easy to overlook.

“The amazing part was that I was from Narrabeen and he was from up the road at Mona Vale and we’d never met,” says Terry Fitzgerald, who first became acquainted with Bruce when he lost to him at Bells Beach in 1968. “But I guess that’s Bruce. To me, he’s always been quietly brilliant in whatever he’s done.”

While working behind the scenes was Bruce’s style, the dirty work at the end of the surfboard production line was hardly the creative outlet he was after. His big break came, of all places, at his home beach of Mona Vale.

In early ’73, Bruce Usher and brothers Phil and Russell Sheppard were working on a surf movie, A Winter’s Tale. They had a problem, however, in wrangling talent to shoot. Channon, being in the mix of it all, knew everyone around. So they struck a deal: They’d show Channon how to use a Bolex 16 mm camera, and he would shoot sessions with the McCoy crew. The movie was a hit, and Bruce disappeared behind the lens. He soon bought a Nikonos camera body, which he took on his annual trip to Hawaii, then found himself traveling the world with Evans as they shot the film Drouyn. Horizons broadened, Bruce returned home to enroll in the Australian Film and Television School. That’s when he got the call.

Seventy-three had also been a landmark year for Hugh McLeod. He married his girlfriend, Judi, in March, then left Australia to travel through Japan and Russia, after which he drove around Europe in a Kombi. For a short time he worked in the commercial art scene in London, before heading back to Australia “homesick and broke.” He set up a starving-artist studio in his flat above Manly Beach. Like Bruce, Hugh wanted a job in surfing. He pitched illustrations to Surfing World, which was by then being published in the city by Sungravure, the color-magazine division of the Fairfax media empire.

“Looks- and sales-wise, the mag was at rock bottom,” says Hugh, bluntly.

When he dropped off an airbrushed illustration to the Surfing World office shortly after returning from Europe, he said in a throwaway comment to editor Geoff Luton, “If you ever want someone to design the mag properly, I need a job.” Hugh, who never lacked in artistic self-belief, was designing Surfing World full time by late ’73.

Hugh had grown up reading Australian surf mags, “but none were an influence on me. As a surfer, I really liked them, but as a designer, I was looking elsewhere.” His influences were coming out of Europe and America: Rolling Stone, Ralph Steadman, Push Pin Studios, and the Big Five. “I loved all of that—the fantastic design and magic artwork,” he recalls. It was a magazine called Communication Arts, however, from which Hugh took his cues. “It was the bible of the advertising and communications industry. High quality and full of illustrations, photography, writing—everything.”

“When I first met him, around 1977,” recalls Derek Hynd, “Hugh was a different kettle of fish. He was very intuitive and quick with observations that most would think cynical, if not for the blunt truth of just about everything he could ever say. In many ways, Hugh was a prime reflection of an Australian influenced by the [Prime Minister Gough] Whitlam years, 1972 to ’75, when to be Australian was to be adventurous, bold, devoid of the white man’s greed that generally afflicted the nation before and after.”

With Hugh’s artistic energy, the fortunes of Surfing World immediately turned. Five issues in, however, Luton pushed management for a pay raise. When the publisher played hardball, Luton walked. Surfing World was thus in need of an editor.

Endless days on an endless coast. Young men making sense of their good fortune.

The publisher wanted a journalist, but Hugh wanted a surfer—someone linked to the scene. The previous issue, coincidentally, had featured a spread from the 1974 Pa Bendall Memorial contest on the Sunshine Coast. The photographer, though, had largely ignored the frippery of the contest and instead captured freesurfing at Noosa. The shooter was a young man from Mona Vale who’d foregone plans to go to film and television school. A good surfer, well connected.

“Next thing I know, I’m the editor of Surfing World,” says Bruce, still surprised decades later.

Bruce’s first issue as editor was May 1974, the same month the Coca-Cola Surfabout was held on Sydney’s Northern Beaches. The richest surf contest in the world officially marked the end of the “country soul” era. Everyone went pro. Coke paid Alby Falzon to film the contest, while Nat Young competed for the first time in years, leaving his farm up at Broken Head and returning, as he put it, “back to the real world.”

Hugh refers to the contests of the time as “the golden egg,” although for Surfing World the riches were more visual than financial. “Just turning up somewhere and hoping for good surfers got old fast,” says Hugh, also a talented photographer. “Competitions provided an undiluted pool of talent to shoot. The skill, picked up in time, was to not make it look like a contest, but an adventure.” The Surfabout contest itself barely featured in Surfing World. “The non-singlet-wearing warmups and lateys were the fertile ground we plowed.”

“These guys combined high-level surfer perspective in building the issues,” says Hynd. “The license was there to see the wheel of contest surfing for what it always was and would be: subjective, narrow-minded, controversial. Perhaps they sought to lure surfers away from competition as much as possible for charity, to take the shackles off.”

Those early years of Hugh and Bruce’s tenure at Surfing World were characterized by a peripheral view of professional surfing. While other mags in Australia and America drank the cola and went tabloid with contest coverage, Hugh and Bruce quietly chronicled it from the fringes. The resulting editorial felt sometimes a little too real.

For example, in September 1975, Tracks famously ran a cover of Michael Peterson holding a surfboard under one arm and a hand-drawn briefcase in the opposite hand. The cover line quoted him saying, “I think I’m a natural born salesman, one of those guys who doesn’t blow anything, just right on.” Surfing World’s rendering of Peterson said less, but was more telling. A simple black-and-white image snapped by Hugh during the 1977 Stubbies at Burleigh laid MP’s vulnerabilities bare.

“Michael crouched for one last cover-up under the shower and momentarily lost his balance, bracing against the stucco wall,” says Hugh. “Snap. I was a bit embarrassed to use that photo for a while. It seemed to reveal a little too much about Michael’s off-field plight.”

Still, it remains one of Australian surfing’s most poignant images, and has been recreated many times on the wall at Burleigh where it was taken.

By the end of the 70s, Surfing World, which had begun life as a commercial and promotional vehicle for surfing, stood at a crossroads. Delineating prevailing culture and counterculture became difficult. The promise of the 70s, for some Australian surfers, had soured.

“There was almost a parting of the ways when pro surfing’s first scent wafted into Australia,” Hugh would later write of the time. “A lot of top draw performers returned to the competitive fold, no doubt hoping long held pipedreams of a circuit would come to fruition. Others took their exile into darker corners. The surfing lifestyle alternative was [to] slave away in the pit, go on the dole, resort to nefarious business dealings…or get a real job. Paranoia seeped onto beaches like effluent in a southeaster. Total waste cases were now part of the landscape.”

Hugh and Bruce played it straight. Bruce’s formative years under Midget and McCoy, both staunchly anti-drugs, was reflected strongly. Hynd joined the magazine as contributor and crusader. Surfing World’s response was to fill the magazine with light.

But while the two had complete editorial freedom, Surfing World didn’t belong to them. “Bruce and I sailed the ship, albeit with a corporate captain,” says Hugh, “and I found out pretty early on I didn’t like working for other people.”

Surfing World was by then being published in the city by Peter Mirams at PM Publishing, alongside avant-garde fashion titles like Belle and Pol. However, Hugh and Bruce soon got a heads-up that PM was going belly-up, and they were advised by a confidante to learn as much about publishing as they could—quickly.

The Flash And The Kill

How a Surfing World assignment killed off a career in insurance sales.

By Derek Hynd

I owe Hugh and Bruce, as I do Terry Fitzgerald.

Bruce and Hugh took a punt on me in their “Ride the Tiger” issue. It bolstered bits of money from Hot Buttered and contests, and pulled me from a nine-to-five sure thing. At the time, SW and Tracks were having their one and only bonding moment.

At stake, the art form.

It was 1977. Pillorying Mike Hurst and his Bronzed Aussies quartet over their “surfing as mainstream sport” putsch mostly united the general readerships. The leg rope had only just been accepted at Easter Bells, parents in support of surfing sons and daughters had rocks in their heads, most city to country beaches had feudal pecking orders, and dogcatchers were being bashed for good measure.

The BAs, though, were thumbs-down for the sparklers after donning velour disco jumpsuits at coastal Sydney’s ES Marks Field 440-yard track. They took a fateful lap of honor before an international athletics assembly gathered to watch world’s greatest miler John Walker assault the mile record when they could instead have chosen to surf at Maroubra, not 2 miles away, and later check “Stubbsy the Elder” spitting the winkle at traffic from his naked rear end. The day summed up the looming great divide of just what constituted core Australian surfing, and the BAs riled the mags to no end.

The swallowed words and mongrel satire of ironed and pressed surfing as the glistening new sport of champions drove a stake firmly against surfing as a predominant lifestyle. However, all that paled in comparison to the full-page SW portrait of the surfer’s surfer, Michael Peterson, at Burleigh Heads, which screamed instability, representing not just Peterson, but a shrinking form where sport, not art, was eating surfing away. Forty years on, it still evokes the mindfuck of shifting sands—the pending death of a subculture.

Later that year, before Christmas, I’d come out of Sydney Uni with an economics degree and was interviewing at stockbroker and insurance companies.

The gut pull of walking into what was Australia’s biggest company, AMP Insurance, was like the anticipation of surf or sex, only more powerful. I was staring into the barrel of 40 years of working 40 hours a week. I went in to be a company man. I came out with a job starting the last week of January. I’d sold them on being their man in a rising industry: surfing.

Bruce and Hugh heard of me going to Hawaii to stay at Jack Reeves’ house and glass shop on the hill above Sunset from mid-December to mid-January.

I’d submitted liner notes in the back of issues for a while, minor pieces on minor things. SW’s “Ride the Tiger” issue, however, was to have me report on the North Shore from multiple perspectives. I was a rookie with my first prearranged assignment.

My first day there was the day after the day of the season, apparently all-time. Greats were coming by to check on boards from the maestro glasser. Word was that Terry Fitz had blitzed Sunset, soul arching and highlining to take the mantle off Reno Abellira at a time when Hakman, Shaun, MR, Hawk, and BK were also peaking. It was the freesurfing art form in full cry.

I then got rotten sick from bad water. I lived on the lounge-room floor on my back, staring at the ceiling for most of the next four days. I’d never seen or heard a gecko before, and there were plenty.

There was a champion beast among them, though.

I called it Rodin. There was a blowfly, too, a really big one. They fed without hassling one another, but then the food pool shrank during chilly weather. So started a battle of wills. When not violently ill, I just watched them, and I still remember the way it ultimately went down.

The blowfly was so mesmerized that it couldn’t get out of Rodin’s hour-by-hour, closer-ever-closer stalking. The luck of seeing the gecko finally claim the blowie was something else—the flash and the kill. I hadn’t put a toe in the sea, but there was the story, the moke and the haole in the wake of Bugs, the BAs, and “Bustin’ Down the Door,” which was still heavy beef.

SW ran the tale, a small story. But Bruce and Hugh were encouraged and asked for more off-the-wall stuff.Thus, with three forms of small income—contests, boards, and writing—I quit the job I never started and surfed my life away. Over 40 years later, point blank, the opportunity at Surfing World was the tipping point.

“We played hardball,” says Hugh of the negotiations to buy the title. “At the time, the Surfing World name itself wasn’t worth a pinch of shit. Bruce and I went in and said, ‘Well, Surfing World is us. We’ve been doing it for five years and we’re just starting to hit our straps.’ We were that confident. We said, ‘Go for your life. If you sell the name to someone else, we’ll just start up another magazine with a different name.’ Mirams owed us a bunch of money, so we pretty much got it for what he owed us.”

The January 1979 issue was Bruce and Hugh’s first as owners.

The magazine’s printers, however, didn’t come with the purchase, and Hugh’s vision for Surfing World needed them. The magazine was printed by Japanese giant Dai Nippon, but the collapse of the publisher had seen Surfing World lose face. After some respectful diplomacy, Dai Nippon struck an all-inclusive deal with the two surfers: paper stock, fluoro inks, die-cuts, foil stamps, you name it.

“The time lag with printing in Japan was a problem, but the quality we got was way ahead of anything, anywhere,” says Hugh. “The main thing was that I knew printing back to front. People look at those magazines now and go, ‘How the hell did you do all that without a computer?’ It was because I knew what the printer could do, especially Dai Nippon. If you’ve got technical knowledge of printing and a bit of creativity, you could do pretty much anything.”

For someone with Hugh’s imagination, the sky was the limit.

“At the height of that whole gonzo-journalism thing that took root at Tracks,” says Fitzgerald, “the counterpoint to the black-and-white newspaper was this sumptuous, beautiful, color picture book. When Hugh and Bruce took over the mag and started reproducing those intricacies of color, that was when I started to see the magic. That Sydney light—four-thirty in the afternoon at Dee Why Point under a low winter sun—was the most amazing light. Hugh would be roaming the sand dunes, looking for a picture to be chiseled from the gloaming, while Bruce was in the water, shooting in this beautiful front-lit studio. Between them they were creating this fantastic visual smorgasbord.”

Bruce and Hugh’s commitment to a full-color, high-concept magazine could not have been better timed considering what happened next: the 1980s.

•

The two kids were fast asleep when the car pulled up out front.

The day before, the Queensland teenagers had made the final of the 1982 Pepsi Pro Junior at Narrabeen and spent the night celebrating in Sydney’s notorious Kings Cross. Gary “Kong” Elkerton and James “Chappy” Jennings had only just gotten back to Narrabeen when Bruce and Hugh pulled up to collect them for a Surfing World road trip. Kong walked out into the morning light, rubbed his eyes, and burped. The boards were tied to the roof, and they drove south.

“We passed straight out,” remembers Kong. “Next thing, we wake up and we’re like, ‘Shit, we’re in Victoria!’”

On that trip, strutting into an Apollo Bay pub, Kong made an offhand remark that would have long-term implications: “If you can’t rock ‘n’ roll, don’t fuckin’ come!” It would be quoted in the Surfing World story of the trip that followed, which featured shots of him playing pinball, eating meat pies, crow-pecking Chappy, and standing on top of an old Valiant wearing red-and-white star trunks while drinking a king brown of Foster’s.

Kong became a cult hero at just 17, and Quiksilver signed him on the back of that trip and that throwaway comment. Because before the surf brands made stars out of surfers, the magazines did. But that dynamic was quickly changing, and the surf industry was rock ‘n’ rolling.

Back in ’79, Surfing World featured a half-page color ad from a backyard Burleigh label, Billabong. “It cost Gordon [Merchant] $180,” says Bruce. “He couldn’t afford the full page.”

He soon would. Hugh remembers sharing a spaghetti dinner with Gordon the night before the latter flew to America with a carryall bag of Billabong samples, ready to make his fortune. Those rag-trade riches never quite trickled down to these humble, backyard surf publishers, however.

“I just can’t believe that we never made clothing,” laments Bruce today, half laughing. “But even if we’d had a crystal ball, it wouldn’t have mattered. We never got rich, but we did Surfing World because we loved it.”

The magazine had no office at the time. It was run between Hugh’s family home at Mona Vale, backing onto Bayview Golf Club, and a spare room at Bruce’s. The master bedroom at Hugh’s became the design studio. A skylight was installed and the east-facing windows were boarded up for better directional light. As the other Australian mags were gobbled up by publishing houses and moved into the city, Surfing World remained the definition of a cottage industry. Bruce and Hugh took the photos. Bruce sold the ads and wrangled the talent. Hugh handled the printing and design. Hugh’s wife, Judi, looked after the accounting and subscriptions. That was it.

“I was the yin to his yang,” says Bruce of his partnership with Hugh. “What Hugh could do, I couldn’t. And what I could do, Hugh couldn’t. There was very little crossover in the middle. We agreed on 99 percent of everything, and when we didn’t, I’d just walk away and go for a surf. And that’s how our business relationship worked for 25 years.”

Bruce describing his role as simply a “nuts-and-bolts guy” might be selling his part in the creative process short. Bruce brought an attention to detail and craftsmanship learned under Midget. But it was Hugh’s artistic swagger that made the finished mag sing. Everything done today on a computer, Hugh did in-studio, in-camera, and inside his own head. He possessed a ferocious artistic energy and skills including, but not limited to, illustration, portraiture, typography, photography, and graphic design. Hugh would hand-draw story titles or bastardize Letraset. He’d splash paint like Pro Hart, immediately shooting the result with the paint still wet. A macro lens brought it all together.

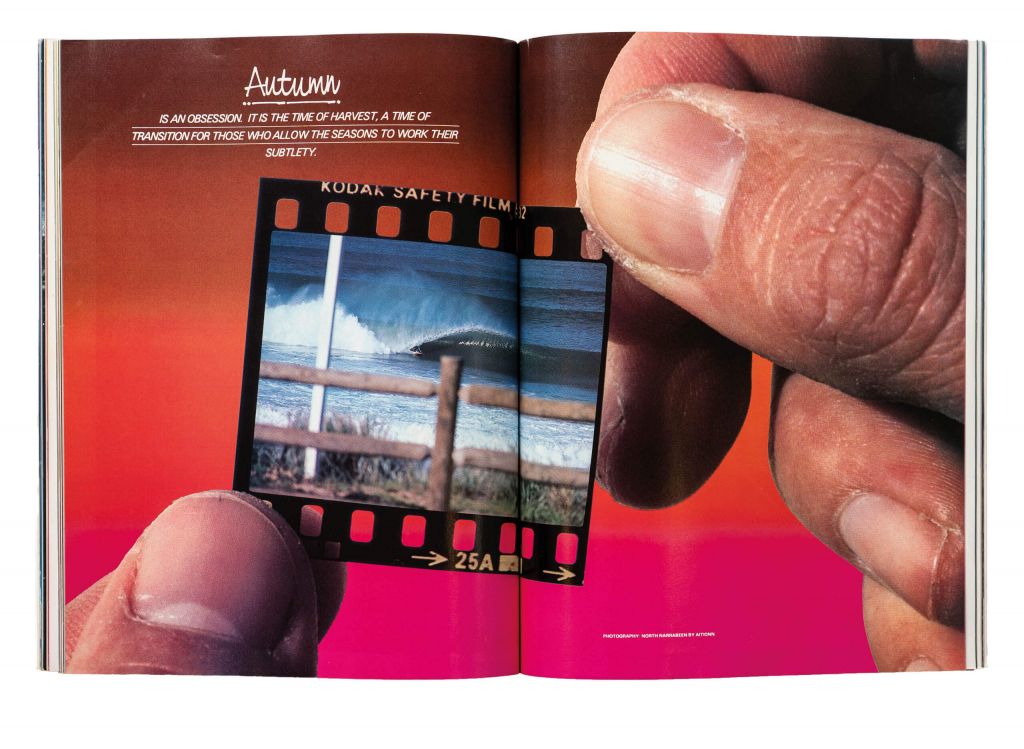

Hugh went through phases. Early 80s design was new wave and geometric. Tilted photo frames with drop shadows broke every classic surf-mag rule. A hand on the page holding a photo slide broke the surfing-magazine fourth wall. Hugh’s 80s color palette was full spectrum. Gradients faded from purple to pink and red to orange. Early 90s grunge eventually became more organic, with textured backgrounds of brick walls, corrugated iron, pandanus trees, and sand dunes. Colors became muted and earthy, Outback ochres and Indian Ocean sapphires.

When the music stopped, Hugh laughs, “A prayer was said and everything jetted away for printing. Some of it was shit, of course, but some of it I quite liked.” While most 80s surf-mag designs aged like milk, Hugh’s oeuvre defined the time. Colorful, bold, boundless. The cover of Ross Marshall staring out at a firing left (or right?) reflected back in his mirrored sunglasses was a high point. The sunglasses had been die-cut by Dai Nippon, the full lineup revealing itself on page three when the reader opened the cover.

Though the magazine dripped fluorescent ink, the subject matter remained grounded, even with surfers then occupying the top of the cultural totem in Australia. “Surfers thought they were King Shit at the time,” Hugh says. “All the girls loved them, and they’d look down on anyone from outside the beach. Whenever you’d hang at the beach, there’d be a hierarchy with surfers at the top. And if you were a champion surfer? You were top of the tree. They were like gods.”

Hugh and Bruce’s mastery, however, was being able to turn the gods into ordinary blokes, and the ordinary blokes into gods. They also tapped back into the same thing Evans had nearly two decades before: the lure of the next headland. This was Australia, and even in the 80s those next headlands were still out there. The road trip, driving through the heartland, became Surfing World’s cultural trope once more. Early forays under Hugh and Bruce headed south to Wreck Bay or Ulladulla, or north to Noosa or Angourie. The roadside diners, service stations, pie shops, and local pubs were featured as heavily as the surf, the photo essays becoming cultural snapshots of the small towns in coastal Australiana.

Their everyman act, though, had one hitch: both Hugh and Bruce drove flash city cars, Saabs—Hugh’s cobalt blue, Bruce’s a deep green. “People used to give us shit and tried to make out [like] we were loaded with money, but they were all secondhand,” says Hugh. “Swedish cars didn’t rust, and we didn’t want to drive a Volvo—a flying brick.”

“Saabs! Eighties Saabs! Can you believe it?” says Fitzgerald. “What were those guys on? But, to their credit, ‘Screw and Loose’ weren’t afraid of jumping in their Saabs and heading off down the South Coast or up to Seal Rocks on day trips, or a week down at Bells. They did a lot of miles, and they’d be there with frost on the sand.”

“Road trips were our deal,” says Bruce. “[We’d] wait for a storm to appear with a slow-moving high behind it, grab two surfers, and go. We’d load up the car at four o’clock in the morning and head down the South Coast. We’d surf somewhere offshore in the morning, and when it went northeast in the afternoon we’d head to Wreck Bay.”

The Occy and Richard “Dog” Marsh trip to the spot in ’86 remains a classic. They arrived at Wreck Bay at dawn, the surf huge and washing through. They returned later in the afternoon to find it still too big. But Occy paddled out anyway. Bruce managed to get off the rocks on his mat to shoot from the channel, capturing Aussie Pipe as big as it’s been surfed. On the way home, Occy fell asleep at the Nowra Pizza Hut.

They squeezed the juice from the day. Both Hugh and Bruce shared a tremendous work ethic and rarely ever surfed themselves on the trips. “We worked our arse off and we came back exhausted,” says Bruce. “Most of them were one-day trips, but we made it look like we were away for weeks. We’d then come back and run 40 pages. You’d get a sense of who these people really were.” Guys like Occy and Kong—already stars—looked like circus animals released into the wild.

“A day trip with Bruce and Hugh, up or down the coast, laid everyone’s personalities so bare that it became an edible trip for any reader,” says Hynd.

The ensemble casts on these trips included underground personalities who had little or no involvement with pro surfing, but who received the same billing as the stars. Surfers like Ant Corrigan, Wayne Deane, Daryl Parkinson, Peter Harris, and, later, Damon Eastaugh.

“Both Hugh and I had an eye for who the really good surfers were,” says Bruce, “and we knew who were good people—the people we wanted in the mag.”

While the magazine had a look, it also had a voice. A Surfing World written style emerged, every bit as reverent to the act of surfing as Tracks was the other way. Word counts were low, but clipped sentences drove hard into the surfing experience. Laurie

McGinness was an early tone-setter, his profile pieces going beyond surf-star hyperbole, such as Tom Carroll, the best junior in the country, featured taking out the garbage bins at home.

Surfing World also found its voice in op-eds and culture jams from Fitzgerald and Hynd, asking hard questions of pro surfing as it became the dominant paradigm. “Through the neon period and those early pro-surfing years, the magazine stayed true to its roots,” says Fitzgerald. “It wasn’t so much reporting, and it wasn’t journalistic or gonzo.…It was written to last. It was more about ‘the view.’”

As the magazine drove further into the 80s, it was a man named Jack Finlay who produced rich-toned poems to accompany road trips and travel features, his words encouraging the journeys inward. They echoed early Midnight Oil lyrics: endless days on an endless coast. Young men making sense of their good fortune.

“Jack tore himself apart to lay down beautiful prose,” says Hugh.

Still, much of the narrative heavy lifting in these pieces was done by the images. “I used to love writing for Hugh in particular,” says Fitzgerald, “because you knew that whatever you wrote would be wrapped around images that would just make your heart sing.”

By design, great swaths of the magazine were left open for interpretation. By saying less about surfing, Surfing World said more.

One writer who did say more was Mario Murdiella. His stream-of-consciousness road journals hinted at secret knowledge. Murdiella, an Aboriginal name for “wave,” was, of course, Hugh. “Some of that Murdiella stuff I’m actually quite proud of,” he says. “You weren’t restrained, because nobody knew who you were.” Hugh also ran his photos under the credit “Aitionn,” the Gaelic name for juniper, which featured on Hugh’s ancestral clan badge.

Through this period, Hugh and Bruce established themselves to be the ultimate behind-the-scenes movers. Quietly assured in what they were doing, they simply got out of the way and let the surfing tell the story.

“There was no pretension,” says Fitzgerald. “These guys were making high art out of their spare room. You respect people for that. With respect, it’s the old adage: You earn what you give. Well, those two guys were the epitome of respecting people for who they were and how they surfed.”

As the 80s rolled on, Surfing World’s horizons broadened again, both geographically and in printed ambition. Their first hardcover book, Surfing Wild Australia, was released in 1983.

“We were over in Western Australia already, down south, when the idea for Bluff trip came up,” says Hugh. “At that stage, no one talked about The Bluff. You weren’t allowed to go up there, all that stuff. But the main mover against it being exposed at the time was Robert Conneeley—from Bondi, originally—and he gave us his blessing. But we never named anything, which worked in our favor wherever we went.”

What started as a surf trip within a surf trip became a statement piece.

“That book completely transported the reader,” says Hynd.

“Australian surfing at the time fed an ongoing industrial rise that cramped, if not murdered, purism in the art form and lifestyle. I reckon surfing was going to the dogs relative to the 1970s. I wasn’t on the trip, but I wrote some words—probably over-wrote some words—hanging out a bit with Hugh and Bruce in their home offices, marveling at the design work and depth of images. The book was their escape. It was a particular chunk of the SW readership’s escape too. The book was a palpable reflection of where Bruce and Hugh as surfer-artists needed to be to escape the national bog.”

Geographically and symbolically, The Bluff represented the last surfable headland in Australia. For the second book, released in 1986, Hugh and Bruce went to Hawaii.

“We went and shot on Kauai without getting kneecapped, which was mildly surprising,” says Hugh, laughing. “We had Tony Moniz with us, who’d brokered the trip, but somebody—and I’ve got a suspicion who—had told all these heavy locals we were coming to expose the place. Titus [Kinimaka] walked by me while I was shooting Hanalei. He didn’t see me, but I sang out and said, ‘How’s it going?’ He came over, and I wasn’t sure how it was going to go. I explained we weren’t going to say where it was. He pointed at the mountain and said, ‘Everybody knows where that is.’”

On the cover of Surfing the Chain of Fire is a lineup of Hanalei, except with the exploding Kilauea volcano stripped in behind Na Pali.

“A lot of things we did were constructs,” says Hugh. “It was like making a movie. You wanted people to go, “Wow, I’d like to go there. That’d be cool.”

Creating a suspension of disbelief as to where these places were became an art form. Coffee Rock, Camp of the Moon, and

Tomahawk Creek all became places real enough to a readership who wanted them to be real. So, too, were the legends of the Yagen Monster and the Curse of the Kilcunda. But in a rapidly shrinking world, as The Bluff campground grew busier and Indonesia gave up her last secrets, the escapism Surfing World once provided began happening in real time. The genie was out of the bottle.

Bruce and Hugh did their thing for most of the 1990s, but their cottage industry soon found itself blocked out by office towers. The surf business grew tall around them, and the introduction of a glossy, aggressive competitor in Morrison Media’s Surfing Life forced them to print in Australia. While the magazine continued to sell, it suffered from “newsstand claustrophobia,” as Hugh puts it. Bruce, who for 20 years had sold ads to old mates with handshakes, suddenly found himself in pitched battles for ad dollars. Competitors started peddling wildly inflated circulation figures. Bruce, too honest for his own good, would show up with SW’s actual sales figures and get laughed at.

The brands that Surfing World helped launch were also changing. Bruce remembers calling Rip Curl sometime in the mid 90s and asking to speak to Claw Warbrick, who, he was informed, was off skiing in Switzerland. He was instead put through to Rip Curl’s new media buyer. “I introduced myself to her. I said, ‘It’s Bruce from Surfing World here.’ There was silence for a second before she replied, ‘What’s that?’ At that point, I knew the writing was on the wall.”

But while other magazines nuzzled up to the marketing departments of the surf brands, Surfing World remained fiercely independent. “We weren’t big,” chuckles Hugh, “but if someone did the wrong thing by us, we usually got them in the end.”

He recalls Quiksilver using one of his shots in Tracks, which was on its own just “uncool.” Soon after, however, as Surfing World was about to send its 25th-anniversary issue to the printer, Quiksilver pulled their ads from the mag. Hugh and Bruce saw it as the brand throwing its weight around. With the issue almost out the door, Hugh had just enough time for a square-up, scrubbing the Quiksilver logo off Bryce Ellis’ board on the cover. Years before Photoshop or computer publishing, Quiksilver was equally infuriated and amazed at how he’d done it.

“Everyone kowtowed to them,” he says, “but it was our magazine and we could do what we wanted.”

Road Song

…strange lights in the sky at the eye’s edge, fingering down and shimmering, mystic and wonderful like Tennyson’s Excalibur leading off through the tundra of tangled vegetation and limestone patterned rockways. Feelings that a million things might happen on the roadsong and no one needs ever know, so we left bottles with messages for people to find. One message said “Fornication ain’t no great sin…” scribbled on a cliff top above a fast peeling left.

Roadsong is knowing that with all the things that can be said “the list” says damn near everything. It’s like a pulse beating back inside and to which all the other things have attached themselves, telling you very clearly that it’s going to take more than just religion to save you.

Days and nights on the road or out at sea beyond the islands and headlands of the coast. Slowly rising and falling. Nights alive full moon silver flights of fancy streaked skies and the ever gentle blink blink blink of a lighthouse.

Barometer falling.

“It’s times like this,” you hear yourself saying, “that I wonder if we shouldn’t pull in somewhere, refuel and check the weather.”

The road can tell you a million things on where you’ve been… vibrations to be picked up like Polynesian navigators who could lie on the floor of a voyaging canoe and pick up the wave feelings from their testicles against the wood… landfalls, eastern light dappling the sea at the eye’s extremities.

Roadsong is the red rust rattle of a ’72 Station Sedan, flashes of colour and snatches of conversation from a South Coast petrol station proprietor looking at surfboards tiered up from the roof.

“We should never have got out of Vietnam, you know,” he’d said, looking at me for some type of response. He pronounced Vietnam as “Veetnam.” “Johnson lost his nerve, and Nixon… Oh, Jesus,” he’d scoffed.

Roadsong is a meridian encircling a state of mind, a ritual of expectation… back seat earphones, bleached bones, and sailor’s ghosts, almost a circus feel wondering what Bruce Springsteen means by “the price you pay,” and if all this movement is taking you to a surfable wave… pillows without pillow cases, the bold tartans inside a sleeping bag all thrown about a confused back seat.

Short morning Australian store stops, out there lounging beneath the gently curved verandahs, windows full with the ancient and timeless ads of that other age, for ice cream, Bex powders, and biscuits. Beyond the door (the road dropping down close by), across the river flat with its dried timber bridge… a line of sandhills. If your hunches are right and your wind senses attuned, the flawless waves of an enlivened ocean are behind those sandhills. Roadsong ends. Anywhere. Nowhere. Everywhere. With hot cross buns dropping butter.

Jack Finlay

Surfing World Photo Annual 8, 1982

By the mid 90s, Hugh and Bruce were starting to look at life beyond Surfing World. They’d been there for over two decades. No one had ever lasted that long at a surf mag. They were both in their forties with teenage children, didn’t socialize much outside of work, and were working more independently on the mag. For Bruce, selling ads had become the competition he’d always eschewed. Hugh, being purely analog, saw the looming digital age as a “computer-jockey yoke.” To this day, he’s never owned a computer.

The duo began looking for an out.

“We heard a rumor that [Kerry] Packer [Australia’s richest man at the time] wanted to buy us, and we went, ‘You beauty,’” says Hugh. “We thought, ‘They’ll give us a bunch of money and we can retire.’”

Bruce, however, spoke to an insider who warned him, “They’ll bleed you for two years to drive down your price, then swoop on you for nothing.”

While they didn’t sell the magazine to Packer, in 1998 they sold it to four surfers from Manly who planned to publish it independently. “It was in good hands,” says Bruce of the sale. “And it was a relief. Hugh and I were at the end of the road.”

As quietly as they’d built their vast Surfing World universe, they resumed their old lives.

The pair had a falling out over some money and didn’t talk for a few years. Hugh took freelance design jobs, but was happy to get out of it before Photoshop was invented. “I’d still be there now,” he quips. Meanwhile, Bruce went back to his first love, longboarding, even editing Morrison Media’s longboard magazine. Their respective Saabs no longer went far beyond their local beaches. Hugh would have phantom surfs under the cliffs at Barrenjoey. Bruce could be found most mornings surfing the Mona Vale Basin.

On one of those mornings, just how completely they’d given themselves to the magazine over so many years became clear. As he watched Bruce in the water, it dawned on Hynd—one of Surfing World’s key figures—that in 20 years he’d never actually seen Bruce surf.

“It was shortly after getting rid of SW,” says Hynd. “He was riding a log at his local rock shelf. First wave, 7 a.m., rock jump into a knee paddle in one motion onto a knee-high wall. My eyebrows lifted. He put in a slight stall and ran straight to a tight five on the nose, feet facing the wall, back foot against front as the wave did a mini pitch-out. He jammed both arms into the face, came out of the little tube dry, and merely trimmed to shore as would Skip [Frye]. Then he casually walked around for another. He had no idea anyone else was around. People talk about Simon [Anderson]’s first ride at Bells ’81 and [Tom]

Curren’s at J-Bay in ’92, but I recall that ride just as well as I recall Roger Erickson at tiny Kammies with his immaculately swift rise to his feet. Bruce and Roger showed themselves as maestros of minimalism. That is surfing. Get that right, get everything right. Anyway, I didn’t think Bruce had surfed in 25 years. Knocked my socks off, and, in many ways, it summed up who he was: humble, self-effacing, loathe to put himself in the spotlight.”

•

Today, finding an old Hugh and Bruce Surfing World is like finding a rare jewel. They’ll occasionally turn up during an archaeological rummage in a back shed, still lustrous despite water damage and being nibbled on by rats. Mint mags are fetishized as collector’s items.

Physically, though, not much of their own archive survives. Earlier this year, Hugh found a pile of old proofs under the house that were beyond saving. Their magazine and image back files have never been digitized. Both talk about how they should get around to it, one day.

Bruce and Hugh don’t see a lot of each other anymore. Bruce lives on an island out in Sydney’s Pittwater, and both remain quite private. Neither has much to do with any kind of surf scene, either. In speaking for this story, Hugh asked how Bob Cooper was going, only to be informed he’d taken his final cross-step in 2020. Neither seems hugely sentimental about their years at the magazine. Bruce’s one concession is a poster featuring all the covers of Surfing World, which he keeps on a bookcase and looks at from time to time.

“All I need to do is look at the cover and my mind goes back to that entire issue,” he says. “I can look at the cover and tell you what’s in every single one.”

Surfing World is still published today, and turns 60 this year. With the recent demise of Surfer magazine, it holds the title as the oldest surf mag in the world.

It’s recently come full circle, changing hands in 2020 for five magic beans, and is being made once again out of a spare bedroom, this time in Torquay. Bruce was chuffed at the news. When asked to pick a favorite issue from his tenure, he nominated the first issue he and Hugh published as their own.

“It was ours,” he explained. “We were really proud that we’d bought it back and that it wasn’t going to disappear. We were both really proud of Surfing World. Really proud. It carried a lot of meaning for us, and I think it carried a lot of meaning for surfers.”

“It created green shoots, both in surfing and in publishing,” offers Fitzgerald of the Hugh and Bruce legacy. “There’s lots of people who picked up one of their magazines at some point and marveled at it, and marveled at surfing. And it wasn’t just Australia. Those magazines found their way out of Australia. Look at some of those magazines that sprung up in Europe, Japan, New Zealand—The Journal† in America. Those really reverential, high-art magazines. I guarantee the people who started those magazines at one point have picked up a Hugh and Bruce issue of Surfing World.” He pauses.

“So the fact that Surfing World hasn’t been lost gives me hope.”

† At Mitch’s that Saturday morning was TSJ’s own Scott Hulet, who would in time take Bruce Channon’s title for the longest tenure of any surf-magazine editor.