Andrew Doheny’s freestanding, open-floor living space in Costa Mesa sits past a dry-docked tugboat surrounded by dozens of warehouse rentals. The 26-year-old has just moved in. The interior is dimly lit, dusty, and sparse. Two-by-fours and sheets of plywood outnumber the furniture. A mattress is tucked into the far corner. A guitar rests against a coffee table. Someone is lumped on the sofa, a blanket covering everything but his feet.

Surfboards are strewn everywhere—shoved into corners, lined up against walls, laid out across the floor. They seem to spill out through the backdoor and lead to a still-under-construction shaping bay. A few are contemporary shapes from the big names. Most, however, are of Doheny’s own design—short, thick, wide, stubby, needle-nosed, flat-decked. The space , Doheny explains, is everything he needs. “I just want to shape and surf—that’s it,” he says. “I just want to figure out ways to have the most fun while I’m surfing.”

Shaping and surfing, for fun, were not always where Doheny seemed destined to end up. He was, put plainly, once a competitive-surfing child prodigy. A preternatural talent raised within walking distance of Newport Beach’s54th Street jetty—in the geographical heart of the surf industry—Doheny’s boards were stickered up in a way that would make a NASCAR driver blush by the time he finished kindergarten. Weekends were spent jersey-clad and, more often than not, ended with a trophy. Regional and national junior titles followed. By the time he could drive, it was almost expected that he’d one day challenge for World Titles.

It was at that age, however, as teenagers are wont to do, that other interests took over. Doheny looked outside of surfing at music and film and art, then began to look back at wave riding through those lenses—as an artistic pursuit itself. Shaping came naturally as a byproduct, as did an approach focused more on creativity than on pleasing a judging panel. He still competed, and found success riding his own boards, but the same motivation just wasn’t there. From a distance, his change in outlook would’ve been seen as a normal development of his own persona. In the confines of the surf industry, his deviation caused brows to rise and questions to be asked.

Not that his talent went anywhere. Doheny’s surfing is still high-performance in the truest sense—a speed- and power-based approach focused on making every turn as on edge as possible in a way that only a few dozen people on the planet are capable. As a freesurfer, he’s refocused his time and energy into channeling progression from different angles, designing boards under his Slob Crafts label, and working on independently produced surf films and web clips featuring himself and his friends, under a banner called Metal Neck.

Surfers who make a living on their image can, from afar, seem to simply have an act.

In person, outside his new home, Doheny seems act free. He answers thoughtfully but with little hesitation, often in a circuitous way around topics from his competitive upbringing and his shift away from surfing for numbers, explaining his transition into freesurfing and how he mapped that as a career choice, unpacking the lessons he’s learned—and is still learning—about shaping shortboards and how that’s changed his own surfing and his perspective on the whole point of riding waves.

WB: You had a pretty successful, contest-oriented upbringing. What do you remember about growing up and being on that path?

AD: I started surfing when I was five. By the time I was six I was sponsored and doing contests. My dad saw early on that I was okay at it and it became my first priority. It’s crazy because almost all of my early memories of surfing are in a contest. It was just straight into it. When I was a young it was a lot of fun. Or maybe I just didn’t know anything else. But I liked the camaraderie of it—it was kind of my school and my social life.

WB: When did that focus start to change for you?

AD: I think I just went so hard at so many contests that, by the time I was 16 or 17, I lost a bit of interest in it. The pressure of getting results got crazy and I couldn’t handle it. What was fun became frustrating. I still did contests after that age, until I was 21 or 22, but the last five or so years of my contest career were kind of rocky. I look back and realize that even when I did alright in contests, I wasn’t that competitive toward other people. I just tried to surf the best I could and not worry about other guys too much. That worked for me for a while but when the results weren’t coming as frequently, I was way too hard on myself. I would lose a heat and just feel like a piece of shit. All the reasons why I loved surfing went out the window. So in order to save my love for surfing, I just wanted to travel and work on my surfing by myself. I didn’t need to be in contests to do that. The thing is, I’m not against contests completely. If the waves are good I’m set to do them. But being on a tour, slogging it out, that just wasn’t for me.

“When I stopped being a hardcore competitor I saw how much contests bring out the ‘jock’ side of surfing. It was such a relief to get away from that. Surfing is an art. It’s self expression.”

WB: Part of that must’ve been just getting to that age though. Like you said earlier, you’d never known anything else. And when you’re a teenager or in your early 20s, that’s when you start experiencing things for yourself and making decisions for yourself.

AD: Definitely. I started to look at things beyond contests and even surfing. Surfing and competing were just everything for me as a kid. I had almost no other interests. It was really refreshing to see what was outside of what I knew. I got really into playing guitar and into punk rock and started a band. I got into drawing and art and making clips. I latched onto those things because I felt like I’d avoided anything outside the scene for so long. Surfing was, and still is, my number one priority. I never lost the enjoyment of it. But when I stopped being a hardcore competitor I saw how much contests bring out the “jock” side of surfing. It was such a relief to get away from that. Surfing is an art. It’s self-expression. It was exciting to get to explore that.

I immediately started working on movies, like the Metal Neck series or web clips, so there was always something to strive for. I started meeting up with other guys that did the same thing, like Creed McTaggart and Noa Dean and Beau Foster and Alex Knost and Christian Fletcher—all the dudes that just liked to rip and have a good time. We do the Metal Neck thing, which is like a family of lunatics who love to surf.

WB: Metal Neck is kind of nucleus for you guys?

AD: We just go on trips, surf, have fun—and film it all. We don’t have a heat in the morning so we can go out at night and just have funny shit happen. We try to make things that are cool, not too serious—just what I think surfing is all about. I feel very fortunate to be able to do what we do. I’d love for us to make another movie soon. I want to make a full-length surf movie that will last. I want to steer away from these one-minute Instagram edits. I think there’s so much more to be seen. Hopefully it will inspire some kids to sit there and watch it for 30 minutes, and then really want to go surf.

WB: Were there any negative responses to going in a different direction?

AD: I think people were probably caught off guard a little bit when I did it. Certain people said that I didn’t want to surf and didn’t care about it. It was the same thing when I started riding my own boards in contests. Everyone was telling me not to do it. Sponsors. Fucking everyone. But riding my boards in heats took some of the pressure off. I looked at it like, if I did well it was a bonus, and if I didn’t, whatever, I was out there riding my own board. Plus, I was having so much fun riding my own shapes and thinking more about the board than scores that I felt like I was free surfing in a heat. I felt like I had something to prove to myself. It’s funny. Once I got a couple of results on my boards, people kind of cooled it on telling me not to ride them in contests.

WB: How did you get into shaping? It seems so rare now when it comes to progressive surfing. I know it used to be the norm, but the guys who self-shape now are mostly making alternative crafts and longboards. There aren’t many surfers who are making their own high-performance shortboards.

AD: That was just one of the artistic aspects of surfing I wanted to check out. I shaped my first board when I was 16. I got a blank, traced an outline, and literally started hacking away at it with kitchen tools and no direction. I had a cheese grater and a Surform and that was pretty much it. It took me like a week, had a concave deck, and was so sloppy and uneven. But it floated and was really loose. It worked. Mostly it just felt cool to make something and get to ride it. The best feeling was letting my friends ride it and seeing them have fun on it. Seeing someone else rip on a board I made felt just as gratifying as riding it myself. After that, I was hooked.

WB: What was the learning process like? In terms of refinement, a high-performance board isn’t nearly as forgiving as a fish or a log.

AD: A high-performance shortboard is the hardest type of board to make because you’re making a board with the smallest amount of foam you can get away with. I’m still figuring it out. It’s just trial and error—cutting away at a blank, glassing it, and riding it to see if it works. I just went at it. I tried to keep my ears open and listen to everyone. Cordell [Miller] gave me tips. So did Lance Collins. Stretch gave me a lot of good advice. I went up to Santa Cruz with John John. We were shaping a board with Stretch and he made me my first template. It was a spin template. And he taught me how to use a planer. That was kind of when my boards started getting more functional. Before that, I was just cutting them out and sanding them down with a Surform, like through the skin. That’s a lot of fucking work. So the planer just belted off, like, five hours of work immediately. That’s when the shapes started to get a little better and more functional.

“I shaped my first board when I was 16. I got a blank, traced an outline, and literally started hacking away at it with kitchen tools and no direction. I had a cheese grater and a surform and that was pretty much it. It took me like a week, had a concave deck, and was so sloppy and uneven. But it floated and was loose. It worked.”

WB: So what exactly are you trying to do with the boards you make?

AD: I try to get as much fishy stuff into my shortboards as I can get away with. I like the paddle ability and speed of broader, thick boards. But you need rocker and you need to turn it, to be able to turn your rail over, so I try to distribute the volume in the best ways I can. I try to get the deck as flat as I can and have it curve from the bottom. So I like to make almost high-performance 80s shapes mixed with contemporary designs. But it’s always changing. I’m always messing up and finding new things out.

WB: In what ways did shaping your own boards change the way you surfed?

AD: I was allowed to go out there and surf the way I wanted, which was to experiment. The boards I was riding before were conventional, high-performance shapes from mainstream shapers. I still ride those boards sometimes—they’re great for a certain type of surfing, the kind I was trying to do in contests. But what I like about my boards is just how flat and fast and how unpredictable and out of control they can be. I have a completely different approach to them. When I ride other people’s boards, I kind of expect them to ride a certain way. But I know my boards are a gamble going into it, so I’m nicer to them. I’ll take the time to figure out how one works, instead of being hard on it right away. I’m fighting mistakes in them all the time, which turn out to be blessings, just learning how to ride a board, even if I don’t know why it’s doing something. Like if a board is sliding out, instead of being over it, I’ll do a turn and then at the last second I’ll push really hard and try to get a rad trick out of it. I’m just interested in making and experiment with different ways to ride waves.

WB: That seems like a good way to keep things interesting.

AD: I’m going to take shaping a little more seriously and see how good I can get at it. I want to keep finding different ways to make trippy boards that will still surf on a performance level. Lately, I’ve had some visions of really going outside the box with fins and stuff, maybe using less fins. Shaping is a way to keep surfing fun. It’s a challenge that I’ll never master—to make a board that works well. There are places that I go in my head with curves or fins that are frightening. It’s just never ending excitement.

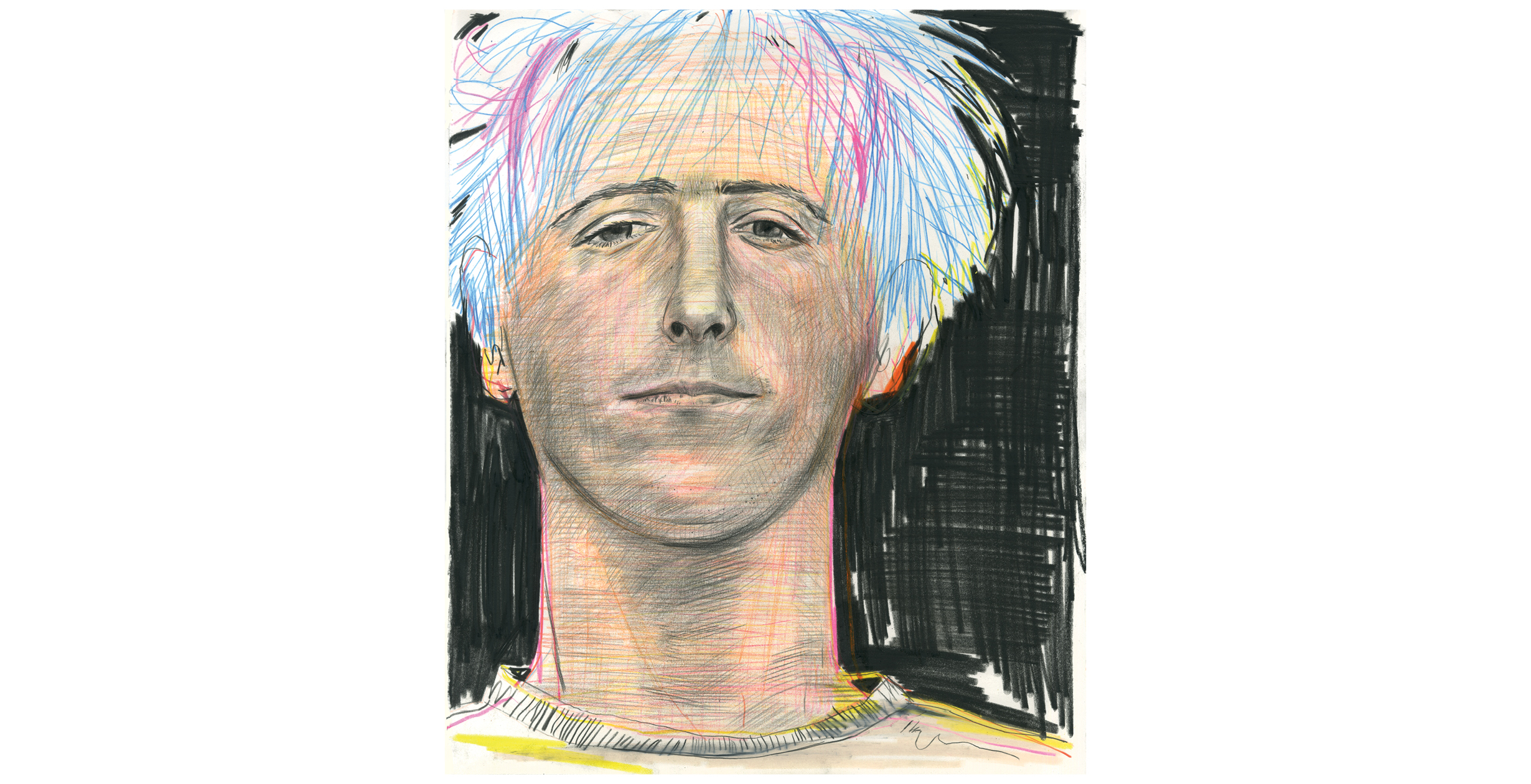

Illustration by Yann Kebbi.