With the advent of the new millennium, there is a technological and monetary plague taking hold of the First World masses—most significantly in America and Japan. Cutting deep into the social strata, it fragments the citizens’ lives and vision of what balance might be. Surprising or not, this virus has gone largely unchecked due to the vested interest of big business and the multinational sectors, because with any kind of negative consumer dialogue, sales might decrease. The media doesn’t want to slap the hand that feeds it so extremely well. So, at the time, there is no mainstream dialog directed at addressing this problem

The predominant theory in America is that the U.S. is the best place in the world to live. The standard of material living may be the highest, but what about peoples’ quality of interaction on a personal or communal level?

Well, the pace of life in America and Japan is like no other on earth. Like, for real, peoples’ lives do not move this fast anywhere else—we are talking serious warp speed syndrome. This pact promotes a complicated living scenario through multiple communication sources, fragmenting daily lives into a sequence of numerous, less meaningful communications. If unchecked and unmonitored, this builds a low quality of life. It’s kind of like only eating fast food and never taking time for a good sit-down meal.

This type of fast-forward lifestyle winds up engaging a “fight or flight” reactive response in our bodies. Thus, our adrenal glands and nervous system work overtime to keep us on track. The adrenals are meant to help us through occasional stressful situations, not the steady onslaught of packed schedules and excessive communications. Without rest and grounding practices, our systems wear down, leaving us with stressed movements and system failure, more often than not creating a situation where happy pills are used to smooth over the symptoms.

I know these perspectives might sound similar to those of people when the black-and-white TV bit into special family radio program time, or when the first telephones changed basic human interaction. You might say, “What is this guy talking about?” Well, when you get off the train like we did in the following venture document, you really see how fast the train you were on is going.

That was the idea of this journey—to go to a place on the other side of the sphere, both geographically and in societal makeup. Life in its mysterious ways would take us to a remote island off the east coast of India named Ceylon, where we would post up, just being there feeling the movement of the place and culture, and sampling the fun peelers of the region. We’d interface with a culture that rises and falls with the sun—a Third World situation where most of the people are engaged in simple manual labor occupations, mainly traveling by bicycle, acquiring food for the day fresh because refrigeration isn’t a big piece of the puzzle. It’s really inspiring to see the cruisiness in the pulse of the humanity and the time they have to spend with each other. There is not much complication in their faces, which is a normal facial posturing in my homeland and with the guy in my bathroom mirror. It’s not that Americans are breaking at the seams per se, it’s just a different way and there is something to be learned from it and adopted.

The following is a visual and scribbled documentation of 20-some days spent in the throes of a culture that is still on cruise control, and of the three surfers and one filmmaker who had the grand opportunity to be there.

—T. Moss

Ceylon

These funny three-wheeled Martian mobiles are called tuk-tuks. Our homies, Richard and Loc Dog, drove us and all of our crap everywhere in these things. Usually, Alex and I rode with Loc Dog, a white-knuckler of a driver with no regard whatsoever for the K-9 species. He would try to run down any dog he saw, which we loudly discouraged. His obvious dislike for dogs made him hate the nickname we gave him, but with time and persistence it grew on him. Besides this one character flaw, Loc was a really cool guy and pretty mellow when the tuk-tuk was not in motion. One big draw was his tape player, a serious luxury item. Some interesting cultural exchange went down: Loc would play us some of his Ceylonian dance action with an occasional Bob Marley set. We had a crazy new waver tape that we played incessantly—The Smiths, The Cure, Tracy and the Plastics, The Fall, The Strokes, and a few more. Loc didn’t seem to mind. We actually became really good friends. One day Loc and Richard asked us all to come to their house for dinner. We said, “Hell, yeah.”

Every extended family member showed up for this meal. They knew the circus was coming to town and no one wanted to miss a chance to inspect and hang with the crazy Americans. We kicked back and talked about our families and they could not understand why Alex, Belen, or I were not married. Alex, at 17, was at a ripe age to tie a big ‘ol knot. We laughed it off and drank quite a few Three Coins beers with their posse. When it was time for dinner, they set the dinner table for four (just for us) and expected us to sit there and eat while the rest of them watched us like germs under a microscope.

“No way,” was our collective response. “Get your plates and dig in.”

It was really cool to see the big, warm family setting and the communal movements to help each other with everything. Richard explained how all his family and friends helped him make his house, like a barn-raising situation. They got it up in two weeks flat. Their basic lifestyle was impressive and, on a simple level, inspiring—so far away from the life I know at home.

—Dan Malloy

Tuk-Tuking in Pottuvil

I’d spent the last five years following the World Qualifying Tour. Each week we traveled to the Huntington Beaches of the world, with 300 surfers riding the same types of boards, doing the exact same type of surfing. Although I was slowly learning how to compete and gradually moving my way through the qualifying series, my surfing had not progressed in three years. I had come to the realization that I was smothering my only passion with my adolescent dream of winning a world title.

At this point I had to decide what was most important. Should I try to fulfill a childhood dream that simultaneously developed with my love for long wheelies and cool stickers? Or should I let it go to fully embrace one of the few acts that would hopefully benefit the remainder of my existence? I made the decision to quit, and for the first time since I was 14, I faced the harsh reality that I was never going to be Tom Curren. In the following months, I felt something new. I was not practicing anymore. I was just surfing. Bodysurfing, longboarding, shortboarding, whatever. I was appreciating what was happening, watching the water go by and enjoying myself for the same reason I did the very first time I angled down the line.

During this transition, I crossed paths with Thomas in Southern California. He told me about his work in progress—a second surf movie to follow up The Seedling and I hinted of my desire to somehow contribute. More than a fan of his work, I had grown to respect his translation of our sport. Two weeks later, he asked me if I was interested in traveling to Ceylon where we would spend a month filming for his upcoming movie. I committed without hesitation. The concept was to drag as many surfboards as we possibly could halfway around the globe, and to capture surfing when and where it happened. This was a far cry from being shoved between flagpoles for 20 minutes and trying to out-shred two Aussies and a Brazilian. The invitation was exactly what I had been waiting for.

I stayed up all night working out the best strategy to transport my pile of gear. I remember my brother Keith laughing at me while I tried to pack an 11-foot Skip Frye, a ten-footer with a huge glassed-in fin, five various-shaped thrusters, a Skip fish, a single-fin, wetsuits, clothes, and everything else you might need for two months on the road. My first stop would be Paris to meet up with Thomas who, at the time, was in the process of preparing his art show. It would soon open at a gallery called “Colette” where he had been for days transforming the bare space of a posh Paris showroom into the colors and textures that make up the walls of his garage in Northern California.

The opening was buzzing with artists, fans, friends, buyers, sellers, critics, skateboarders, and the odd passerby. Journalists and photographers snapped photos and scribbled notes while young artists marveled at the compositions. After the show, I could see that Thomas was pleased with the turnout and relieved to be done. We were both eager to be on our way.

Thomas had two surfboards, multiple Pelican cases filled with camera equipment, a duffel bag, a huge tripod, and a cooler full of film. Our volume of luggage was absurd. When we handed over our tickets to initiate checking in, airline staff began to notice the piles behind us. They tallied the weight of every unit, piece-by-piece, adding up each kilogram. While the lady made her analysis, Thomas and I peered over the counter like 16-year-old kids not sure if they passed their driving test, she looked up and told us that we would have to pay almost four thousand dollars in excess fees if we wished to board the aircraft. Before long, we were speaking with the manager. If there is one thing I have learned about traveling, it is that being polite in airports will leave you broke and in transit. At this point, we were getting desperate.

Our greatest concern was getting to Colombo before Alex and Belen. At the time, the American public was being force-fed a daily dose of terrorism via the news. Alex’s parents were not real excited about his departure from U.S. soil. They trusted Thomas and gave their consent only after he promised to keep a watchful eye over their son. Belen, on the other hand, could handle herself on the road, but we knew that Colombo wouldn’t be the safest place in the world for a single white female with blonde highlights, especially one that doesn’t mind showing a little skin.

The situation was getting heated as the plane started boarding. I found Thomas keeled over in the comer, pale white. He was bent over grabbing his stomach. I thought he was going to vomit. I remember thinking to myself “Great, we aren’t getting on the fight and Thomas is having a nervous breakdown.” His state caught the attention of the manager who asked if my friend if he was okay. Then, I caught a strange look from Thomas: “Dude, I’m just acting. Tell that jackass to put us on the flight or I’m gonna croak.” The manager barred us still.

We realized that the only way that Alex and Belen could get the help they were promised was for Thomas to immediately board the aircraft without me. I reloaded the car and began my search to find a cargo company that would freight our gear for less than four grand.

Two days and $1200 later, I was finally on my way.

I stepped out of the airplane and onto the hot tarmac.

It took almost three hours to clear our boards and camera equipment at the shipping company. By the time we were finished, we had a stack of official papers that were as thick as a bible. They had been signed, stamped, resigned, triple checked, and finally cleared with a 20-dollar handshake. Thomas organized a bus to make the long drive to Arugum Bay, which would take us all the way from Colombo to the southeast tip. About six hours into our drive, streetlights and houses became sparse and our driver looked a bit worried. He told us that there were bandidos out in the boonies and that he was afraid.

We weren’t in the mood for being held up, so we found a place to crash. The next morning, we drove another six hours on a half-paved, pothole-infested road. We caught our first glimpse of monkeys, water buffalo, and wild elephants, and soon enough, we were approaching our destination. When we finally saw the ocean, we instantly lost our composure. Whitewash was visible in the distance as we passed through the small town of Pottuvil. We all sat on one side of the bus, faces pressed to the windows, yelping, “Look at that one!”

We weren’t looking at a proper wave, but none of us seemed to notice—our imagination had turned a terrible little roller into a perfect peeling right. We found a place to stay and grabbed our biggest boards. On our way to surf, we got more than a few amused looks from the villagers. The sun blasted our pale skin and the sand singed our haole feet. Equal parts excited and in pain, we hollered and yelped as we frantically hunkered our logs through the fishing village and down to the beach. I’m pretty sure locals had also never seen surfboards that big and they had definitely never witnessed people so excited to surf the worst wave in town. But the definite spectacle was Belen and her scanty (for Ceylon) bikini.

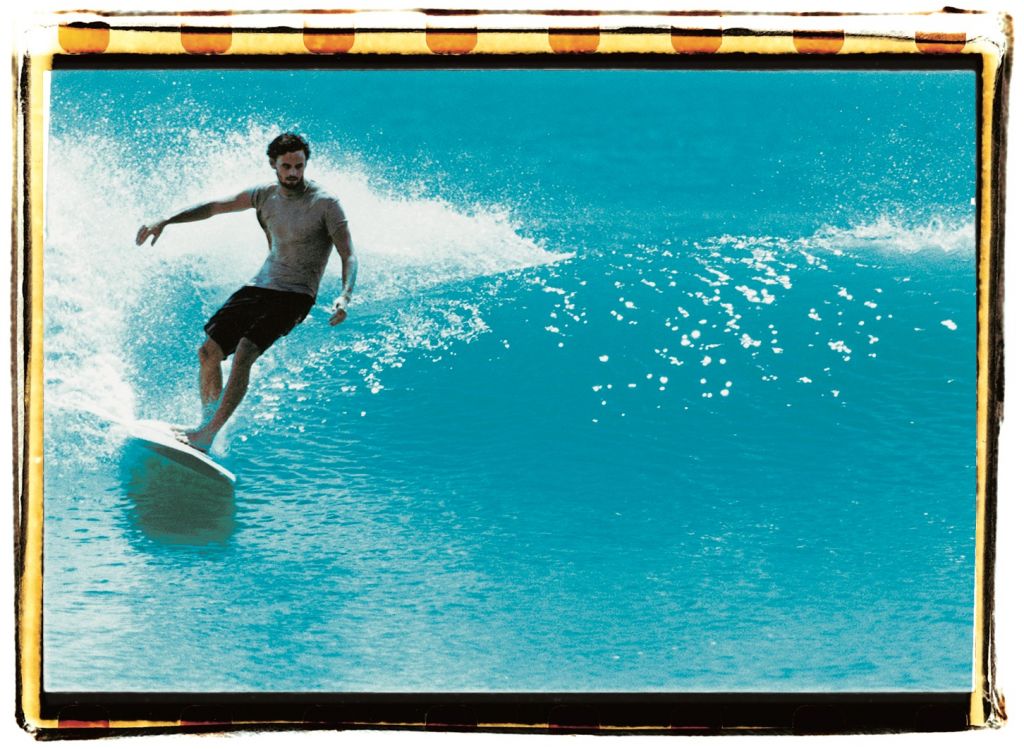

The waves broke just off the tip of a sandy point and then dissipated into deep water. Alex and I jumped straight in, knee paddling from the bottom of the bay, while Thomas and Belen ran past the fishing boats and up the point. We spent the next two hours gliding the travel tension out of our systems. It was amazing how much better my 11-foot Skip flowed through the water than it did through airport security. For the first time since our journey had begun, the big green beast was at home and carrying me.

That evening, we unpacked our 17 Surfboards. Almost every board varied in shape, size, and concept. As each one was freed from its cocoon of board bags, bubble wrap, foam, and tape, it was passed around in a shower of “oohs” and “aahs,” each one of us feeling the rails and curves while listening to the proud owner tell of its origin and what conditions it worked best in. Thomas pulled out a yellow, blunt-nosed quad crafted by Rich Pavel. Alex unveiled a collection of fins he had custom made for the trip and I showed them one of my favorite boards, a hybrid 80s Merrick thruster.

The roosters would crow before dawn. Soon after fishermen, old and new, would gather at the beach to help each other carry their vessels into the water. Our wake-up cue was the sputtering of tuk-tuks as they rounded the corner to pick us up. I would roll out of bed in my boardshorts, still salty, sandy, and sunburned from the previous day. Thomas walked outside with a full load of camera equipment while I grabbed a few leashes to tie our boards down. We then ousted Alex and Belen.

A tuk-tuk is basically a scooter with three wheels and a thin tin cover. The name of the pod-like vehicles was derived from their horn, which is applied every three seconds regardless of the situation. They were our only form of transportation. They could just barely handle our massive surfboards and each one had just enough room for two passengers. Barely secured by a leash, our boards swayed like weather vanes as we bounced along the road.

Belen and I rode in the older tuk; its engine sounded like a worn-out lawn mower on the verge of stalling at any moment. Every morning we loaded up quickly, stopped by the little bakery to get bananas and pastries, and then sped off down the dusty road to Pottuvil Point. It was a bumpy ride swerving between potholes, cattle, and school children. Little boys and girls wearing white and navy-blue uniforms lined the road, walking hand in hand to the schoolhouse, and quickly gathering off to the side, laughing and waving as we passed. Other kids ran from their houses just to catch a glimpse of the funny white people who would go to the ocean each dawn and then return home in the evening without a single fish. We stuck our heads out waving, smiling, and making faces. Their excitement was genuine and their smiles contagious.

One morning, Belen and I had a competition to see who could get more high-fives while we sped past the children. She gathered 23 and I lost out totaling 21, being robbed of victory when a few of the grommets on my side bashfully snatched their arms back just before we connected. They would run away covering their smiles with both hands, laughing as they hid behind their big brothers and sisters. We looked back, waving goodbye until we disappeared around the next corner. As we made our way out of town, the dirt road below us gradually began to blend with sand. Monkeys would dart across the fields, stopping to stare at us suspiciously. We drove until the sand was too deep and then unloaded the surfboards and camera equipment.

Unlike most kids from California, he’s been influenced by more than one of surfing’s eras. It was tough to decide what shaped him more: his weeks hanging out with Robert August in Costa Rica, the air launching grommets in his hometown of Newport Beach, or the countless hours he spent studying guys like Joel Tudor and Donovan in surf videos. Despite his many mentors, he has a style all his own, never failing to accent each movement with his patented hand jive and body English. Alex is a true surf rat. —D.M.

Our driver, Richard, would then ask “Coming going?” which was his way of saying, “What time should I come back?” He only knew two phrases in English: “Coming going” and “Going coming.” It was all he needed, and we quickly learned what he meant.

We asked Richard and Loc, our other driver, to come back in five hours, and then we hiked over the sand dunes and down to the beach. We each carried two surfboards and a backpack filled with water, food, wax, and sunscreen. We would then post up next to one of the small white-and-red fishing boats that lined the sandy bay. We learned that the sliver of shade created by the bow would be our only refuge from the scorching sun. Less than 50 yards away perfect rights peeled along the sandy point. We piled on the sunblock and hit the water for our daily marathon session. The waves reminded me of the Gold Coast in Australia and at high tide a side wedge would bounce off of the beach and push quickly through the inside section. It was tube riding, slip-sliding heaven.

Like clockwork, fishermen spread huge nets just outside of the surf line, and all of the village grommets would line up on the beach to pull them back in. When the children weren’t working, they were playing in the shorebreak and bodysurfing with broken pieces of plywood. If one of us lost a board, no less than eight grommets would plow each other over in pursuit of a try. Within seconds, about eight kids would be clinging to the board like leeches and they would not let go until one of the big boys would come over and pull rank. After all-day surfs, we filled our bellies with fresh roti and blazing curries.

—Dan Malloy

Paris Breakdown

Last night we experienced Cuban music in real life. We stopped at a little yellow restaurant for a bite to eat. Just before we ordered, I watched half of the people in the place gather into a comer with two strange guitars and plenty of things to shake and beat. I wouldn’t call them a band; they just looked more like friends. What they played didn’t sound like music—it sounded like a perfect explanation of how amazing life is. They used the sounds to bring us all together and to turn a roomful of normal people into something larger than life. It blew my mind to hear sounds that full and alive. It seemed somehow that history filled every gap, driving the rhythms to a place I didn’t know was possible. For the first time, this made me aware of how dry and self-important the things I listen to at home are. Mostly middle-class white kids using amplified microphones to make sure everyone in the room hears how sad they are. It made me never want to hear that self-important music again. Then I realized that I really love some of that whiny bullshit—it truly reflects what we lack.

Bouncing between the First and Third World causes severe cultural whiplash. I mean, after the not-so-risque female attire in Ceylon, the streets of Paris seemed like a perpetual catwalk of scantily clad women. During our second stop, we met up with T. Campbell’s good friends, Ed Templeton and Rick McCrank. Ed was preparing his massive body of artwork at a museum called the Palais de Tokyo. His work consisted of paintings, photographs, and words that he had compiled over the last 10 years as a professional skateboarder. It is not exactly the type of art that belongs on the front of a Mother’s Day card, but his work is a realistic counterbalance to the glamorous pop media of our time, and it forces me to rethink what I know. The museum was also hosting a skate demo for Ed, Rick, and some other pros that were passing through. Like a 10-year-old at his first Blue Angels air show, I watched as the skaters launched themselves off huge concrete stairways.

I even got to hang out and ask them dumb questions, like, “How high can you ollie?” They reciprocated with their own dumb questions, “What’s the biggest wave you’ve ever caught.” Our paralleled ignorance was a reminder that skateboarding has long lost its roots in surfing.

Paris is a “no plan needed” type of city. With a decent pair of walking shoes, a few bucks, and an open mind, the opportunities are endless. Every day we seemed to find a new line of museums, parks, restaurants, and cathedrals. Although Paris was a nice fix, we were already fiending for something a little more tidal, and with rumors of a new swell pulsing through the Atlantic, our plotting began. Mundaka was not an option since the top 44 had just occupied it. It seemed we were surely bound for the beachbreaks in Anglet when, at the last second, Thomas had an idea. He slipped into a small travel agency and quickly returned with eyes beaming. Morocco was a four hour flight and less than three hundred dollars away.

—Dan Malloy

Morocco

Morocco is a fairly arid piece of Muslim real estate lying on the northwest corner of Africa. If someone kidnapped you and dropped you out on a remote section of the Moroccan coast and you had no idea were you were, you’d probably guess Baja—similar vibe, dusty, windswept shrubbery and sandstone cliffs. The landscape is similar, but that’s where it stops—the culture in much of the country can send you back 200 to 1,000 years in seconds. The roles of the society are extremely defined by Islamic and cultural tradition. The men are outside doing their work or lurking with the homies. The women take care of the interior home duties. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of mixing until they are forcibly joined in holy, pre-arranged marriage. These divisional roots tend to cause a certain amount of angst in the populace. It’s most noticeable in the men, as they are really the only ones that you communicate with. In the countryside, women are all wrapped up in garb and usually the only parts that are seeable are their eyes and hands, which get the royal decoration treatment in a desperate attempt at self expression—a beautiful one at that. Eyes are caked with mascara, and hands are temporarily tattooed with henna, a plant that’s smashed up and mixed with water into a paste and then applied in extremely intricate patterns onto the hands and feet. The henna is usually applied for specific cultural events like weddings and funerals and other rights of passage—whatever the moment, these ephemeral designs are pies for the eyes—so beautiful.

Due to recent and not so recent global events, Muslim cultures by association are seen as enemies or bad people in the eyes of the American media and general populace. This is flat out, straight up, not the truth. People are people. Whatever god you have— be it man, woman, blue elephant, or the common “it”—may it bless you and bless all beings, humans included. We are all on this spinning blue, green, and brown ball together. The sooner people and governments move toward an idea of respecting the earth and its inhabitants as a singular entity, the closer we will be to having any chance at a sustainable future.

Back to North Africa—I had spent some considerable time in this neck of the woods over the Last 10 years and had always dreamed of capturing some of the ridiculously good looking (Zoolander ref) point breaks that dot Morocco’s rugged coastline. Dan and I had been traveling together for six weeks by the time we reached a little beachside town in the south of Morocco. Immediately upon arrival, we got in the water at one of the most well-known point breaks in the region. There were four guys out and the waves were a few feet overhead—warm water for Morocco, just a wetsuit top and trunks—backlit bliss treatment. I could have been filming the really pretty lines Dan was drawing down the point on the 5’10” Skip fish, but I had to surf, and it was so good to be back; half dozen, full-belly screams were released into the Moroccan sky—serious rejoicism. The swell was not really doing it for the next few days, so we caught up on the sleep we’d been avoiding for some weeks. Our bodies just said, “This is our turn.” Full-blown nappa morti. A few days later we went looking up the coast to see if we could find a little something at this reef point-breaky type deal that some refer to as Hash Point. There was a whole host of French, top-to-bottom, serious whackers out there, with veteran lensmen capturing every critical slash. Dan paddled out and realized he knew some of the guys from his tour days.

Dan got a few; that’s where this big photo came from. When you travel out onto an African limb like we did, here’s hopin’ you don’t have to spend your day trying to be Willy Shoemaker among the other talented jockeys. By looking up the point from our place of rest, it seemed as if the swell had bumped up a bit. We got back in our tin can of a car and headed back up for the late afternoon to H. Point. Holy moly—emerald walls of joy, and really no one out—just a motley crew of Euro action who weren’t that interested in the double overheaders; just enjoying the singles. Our group of French wave technicians were nowhere to be seen, hallelujah. Dan’s dynamics were only captured by the motion picture camera for said film, so you’ll have to engage the fleshy parts in your skull cap; super backlit greenies, just ropin’ in six-wave sets, martinis on a little float out the back, super-duper majestic. Thank you to the North Sea.

That late afternoon was why we went to North Africa.

The quality of the water bumps comin’ off the sea pooped out, but such is life and in the grand scheme of our two month expedition, we laughed a lot, cried multiple times from that laughing, rode a large assortment of boards, waves, and cultural strata, burned our tongues off and put them back on, and now all we had to do was go back to France for a few days and we were home free. Life is very good, and we are so ridiculously lucky to be surfers. PERIOD.

—T. Moss