Chris Malloy:

I called Jeff early one morning from a gas station in San Pedro. I was lost and frustrated. A few weeks before, we had stayed up until two in the morning talking and scheming about The Coast, a scary, beautiful stretch of coastline full of empty valleys and legend. Jeff has talked about it since I’ve known him and every year we’ve come closer to committing to it.

I woke him and he must have been startled to hear my first words.

“Jeff, let’s go. Let’s do The Coast.”

“What, huh… Who is this?”

“It’s Chris. Let’s start gearing up now. We can leave as soon as I get home at the end of this month.”

“Are you kidding? It’ll be November—the surf and currents will be out of control.”

“Jeff, you said it yourself, there’s plenty of food and water back there. If we have to wait out a swell or two, who cares?”

“Where are you?”

“I’m stuck in LA. It’s hell. Just tell me you’ll consider it so I can dream about it until I get out of here.”

Jeff’s tone changed from bewildered to dead serious.

“Chris, don’t worry about me. I’ve been ready since I was 15. Just get over here and we’ll leave the next morning.”

I got back in my truck and pulled out of the old gas station to keep looking for the 405. The conversation I’d just had with Jeff seemed surreal. I hadn’t planned the call. Somehow my mind was on the brink of disaster with cellular units, traffic, red lights, green lights, coffee, and brown sky. A survival switch was flicked on in my head. Every hour until I got home I dreamt about the endless mountain ridges and wide open ocean.

Jeff Johnson:

I caught a glimpse of The Coast from an airplane window when I was about 15. It became this mystic haven for my dreams and ideas. I became obsessed with ideas of how The Coast should be done. I asked questions. I bought charts and maps. I sorted through my collection of gear. I packed, unpacked, and re-packed my bag. I even tested different methods of water travel. I scrutinized my goggles, my fins, and my boardshorts. I wanted us to be ready for whatever The Coast had to offer.

We wanted the process to be simple and our bags to be light. By studying the charts, we found that the majority of The Coast could only be done by way of water, which meant we had to somehow pull our bags while we swam. Dry bags don’t float and they create too much drag. We needed to find some sort of flotation device that could easily be packed and unpacked throughout our journey. In an old surf shop, we found the perfect transportation devices: vintage canvas surf mats. They had been on display so long that the plastic wrapping crumbled when touched. The color was faded where they had been exposed to the light. We bought all of them and it was money well spent. The surf mats soon proved critical—we were to sleep, surf on them, and haul gear across the ocean with them.

Chris and I ended up driving around Honolulu collecting necessities for our trip. We stopped in at Downing Surfboards, one of the last shops catering to the well-rounded waterperson. There was a chance that the legend himself, George Downing, would be present and maybe we could pick his brain.

We were in the back of the shop sorting through dry bags when I noticed a door ajar, revealing a man at a desk. It was Mr. Downing. He had been listening to our conversation. He slowly opened the door and I could see the sparkle of interest shining through his eyes.

“Can I help you boys?” he said.

For a moment we were frozen. Here was a man who has done it all: from redwood to balsa, balsa to foam, tankers, guns, catamarans, canoes, Makaha, Waimea, Publics, and Queens. A true dedicated waterman through and through and he asks us in the most humble way: “Can I help you?”

There was a silence and one of us eventually said, “Ahh…yeah.”

We told him of our plan and the way we wanted to pull our bags through the water.

He thought for a while and rubbed his chin.

“You need to rig your rafts with a v-bridle system,” he said. “It will keep the forward part of the raft out of the water and planing”

I watched as he faded through the paddles and boardshorts, racks of single-fin guns, wax, wetsuits, and aloha shirts. He opened his office door, took one look back, smiled, and disappeared.

I was sitting on boulders in a dry cave above a crescent-shaped beach. Dark squalls marched down the coast, depositing rain into the dense valley behind us. The water wound its way through a maze of black cascading pools and stone. Slowly, the water seeped through the sand, ultimately meeting its place of birth, the ocean below. The evening sun danced around the clouds as Todd and Chris bodysurfed the day’s remaining waves. The swell had increased throughout the day turning the cove into a boiling tub of tripled-up nonsense. Unless the future holds revolutionary advancements in wave riding equipment, these waves will never be ridden on conventional tools. For now, the body will suffice. The body alone.

During a break between bodysurfs, the four of us hiked into the valley to find food. Our rations consisted of one energy bar, one can of tuna, and one small serving of brown rice, per day. The rest we would find in the ocean or in trees.

The valley provided us with an unlimited amount of guava. We shook trees, scoured through the undergrowth and gorged ourselves on the tasty fruit. We found some peculiar looking nuts on the ground. One of us began cracking them open for inspection. They looked fine: smooth, white, and oily. Still unsure of them, we limited ourselves to one or two each. We filled our hands with more guavas and descended back to the cove. We wanted to get wet before dark.

On the way back to the beach, we found ourselves hungry again. Guava fruit has a slimy pink pulp inside that is littered with tiny white seeds. It tastes great, but does nothing for an empty stomach. The fruit only postpones the body’s craving for food. It’s a tease, like methadone to a heroin addict.

It was almost dark and the rain had come. Large drops of water fell from the mouth of the cave. We were scattered throughout the cobblestones with our headlamps turned on. We decided to sleep there on our surf mats. All of us were silent, listening to the sound of the rain and the wind. The surf bellowed beneath us.

“Todd,” I said.

“Yeah?”

“I’m trippin’.”

“Yeah, me too.”

“No, I mean… I feel weird, like I’m high on something.”

“I know. I feel it too,” he said. “Could we be that tired?”

“You think it’s those nuts?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

One by one, our lights went out. Our bodies were beat—plenty of exercise and very little food, mostly guava. I zipped up my jacket and positioned myself on my mat. The rain had stopped. A large set boomed in through the cove, sending an echo through the cave and up the valley walls. A light breeze swept in around me. I heard someone whisper something to someone else. I was awake, then I wasn’t.

Morning came on slowly, with the soft glow of a rising sun. There had been intermittent squalls throughout the night giving way to the brightness of a new day. We rubbed our cloudy eyes at the sight of what looked like a larger swell. Not taller, but thicker and rounder with exaggerated focus. We looked at each other in awe. Could it be any crazier than yesterday? Quickly, we threw down a few leftover guavas and took tiny bites of energy bars.

Within minutes we were fighting rips, bouncing off the bottom, launching ourselves over the falls, and occasionally sliding through crazy tubes. Suck-outs, suck-ins, double, triple, quadruple-ups. It was a freak show of infinite liquid mass. Some waves met with rebounds coming from the base of the cliffs while others simply met with others to join forces.

These waves were nearly impossible to ride, so we opted for the next best thing—a view from the front row. It was enough just to be close to these things to watch, listen, and feel their astounding energy. The smaller more manageable waves were ridden with a 50 percent success rate, giving a completed wave twice its glory. Whatever the outcome of each wave, ridden or not, we all became an audience full of cheers. The hours of incessant hooting left us with hoarse voices.

There is a pattern along an all-day hike that keeps repeating itself. We’d follow a series of switchbacks to the base of a valley, cross a creek, switchback up and into the next valley, more creeks, another valley, another ridge, then a long series of switchbacks to the ridge that we had previously seen. This process could take hours. We kept expecting to see some change or an end once over the upcoming ridge, but there would only be more of the same thing. This went on all day.

At one point, Chris and I found a comfortable pace and pulled ahead of Seth and Todd. After an endless uphill push, we sat down to wait and replenish our strength. We were tired, sore, and hungry. There had been plenty of guava along the way and we ate them whenever possible. Whatever we could do to keep from eating our daily rations. But we needed more. We noticed an area beside us littered with those peculiar looking nuts we had eaten earlier in the trip. We grabbed handfuls of them and began cracking them on rocks.

We knew nothing about living off the land, but we felt we were accomplishing something in this fast-food age.

There were areas where water seemed to come from nowhere. It seeped through cracks in the rock and slithered down crevices only to meet with more of its kind forming a stream. This stream would gain momentum toward a cliff so high that its water was reduced to a mist before hitting the ocean below. The day marched on till we could see no end. Eventually, we stopped on a ridge overlooking a magnificent valley. It was much larger than any of the valleys we had previously seen. There was a long white beach at the opposite end and the beach was where we wanted to go. I pulled Chris aside.

“Hey,” I said, “I feel like shit.”

“Me too. I feel really dizzy.”

“I’m gonna have to puke, I think.”

“I know,” he said. “It’s bad. I can feel it coming up.”

“It’s gotta be those nuts. They’re poison or something.”

“Yep.”

I looked at Seth. He didn’t look so good.

“Are you sick?” I asked.

“Yeah, I feel horrible.”

We beelined it down to the valley. through a couple of streams, and followed a bluff along the beach. By now, I had tunnel vision with little stars bouncing around my peripheral. My stomach was convulsing and cramping. I tried to run but couldn’t. When I arrived at what seemed to be the end of the beach, I gave in. Shit, I thought. I should’ve known.

Todd Sells:

Being a swimmer, I was anxious about the upcoming water portion of the trip. Whether it is true or not, I felt responsible for making the swim safe and successful. My self-appointed task was fairly daunting for many reasons. Though I was confident in our abilities, there were three specific but related unknowns that concerned me: our ability to tow our gear as we swam, the exact geography of the remaining coastline, and the currents.

As for our mats, only Jeff had actually tested rigging and swimming with his gear. To our surprise, he told us he had had success with simply tying one end of a common surfboard leash to the raft and gear, and strapping the other end to his ankle just like he was surfing. What we didn’t know was how hard it would be to make progress with a 40 lb. dry bag in tow, how the rigs would handle large wind chop, and, finally, how we would get them in through the surf.

We didn’t know the exact distances between the valleys we were planning to stop in. Nor did we know what they looked like, if they were accessible by sea, if they had water, or if they had anything edible in or around them.

As for the current, Jeff had gathered enough information to surmise that—barring a large storm or swell—the prevailing current should be with us for the first two thirds of the swim. We guessed that the last third of the journey would be, at best, slack current. At worst, the final leg of the swim would stop us dead in our tracks or sweep us out to sea.

We knew that a good swimmer could cover a mile in about 20 minutes with no gear or current. Even our rudimentary math skills allowed us to calculate that a current of 3 mph was going to take us whichever direction it was going. If that direction happened to be out to sea, that was where we were going.

Once there was enough light, and the others started nervously fiddling with their gear, I went for a free swim. The waves were easy to negotiate with only my goggles, but promised to be challenging with our rafts and dry bags. When I got outside the surfline, looked back to the shoreline to check out how fast I was drifting. It was 1 to 2 mph in the direction we intended to swim. I looked toward shore. Our makeshift campsite was on the sliver of white sand at the base of a 300-foot black sheer cliff. The roof of our cave was actually just the overhang of the awe-inspiring cliff.

The combination of the scenery, the energy in the choppy water, and the anticipation of the day ahead produced in me an adrenaline rush that I could not control. When I slowed enough to regain my composure, I realized that I had covered the distance to the cove: it had only taken 10 minutes to go almost a mile!

The fact that the swim back to the campsite took nearly 30 minutes confirmed that the current was in our favor. The good news was that it would be easy sailing. The bad news was that turning back would be impossible. Once we launched, we were committed!

Back at the campsite, the boys were busily preparing themselves and their gear for our day of swimming. We took a couple of last looks at the charts Jeff had brought. I tried to reconcile the coast I had just seen with the sketches Jeff showed me. We each drank the rest of our water and refilled at the nearby stream remembering, of course, to add our iodine tablets to make it potable.

Having spent most of my life in and around pools, I long ago lost any fear (and homophobic underpinnings) of the dreaded “Speedo.” As such, I rarely find any humor when I do see a guy in a Speedo. But seeing Seth, Jeff, and Chris carrying their stuff down the beach, I couldnt help but crack up. They are not Speedo guys. The boardshort tan lines, combined with surf mats, masks, snorkels, Zinc Oxide, rash guards, fins, dry bags, duct tape, and leashes made for one hell of a funny sight. As we ridiculed and laughed at each other, we made our way into the water.

Just as on the trails, we fell into different rhythms and paces. Chris and I took an outside course while Seth and Jeff hugged the cliffs. The scenery under the water was slightly disappointing, but the view of the land was nothing short of overwhelming. Ridges and valleys similar to the ones we had labored to hike breezed by as we swam with the current. Chris and I were relieved to learn that, for the most part, swimming while towing our rafts and bags was working surprisingly well. Even in choppy water our rigs only occasionally capsized. Mostly, they just rode the chops and lugged on our legs once in a while. Jeff and Seth opted to ride their rafts. As they kicked and paddled, they were able to take in the spectacular scenery above the water.

We regrouped as we approached a point and a promising looking cove. As we discussed the pros and cons of going ashore, we found ourselves caught inside a head-high set breaking on a fairly shallow and sharp coral reef. I think we all got worked, but somehow I got the worst of it—a gash on my knee, a hole in my raft, and the loss of my three prong spear.

Jeff Johnson:

You can’t duck-dive a surf mat and a dry bag. Once a wave hits you, you can only hold on for the ride. The surf was overhead with little peaks scattered here and there. We weaved our way through them and it was just a matter of chance if and when you got hit. All of us got drilled, but Todd got the worst of it. Chris was balancing on the reel when he saw Todd’s gear coming toward him and no Todd. The raft popped as it bounced across the reef leaving a yard sale of gear behind. Todd was left with a minor cut on his shin and his spear was never found. It could’ve been any one of us.

After surveying the area, our actions became automatic. No questions asked, no words spoken…just duty. We needed food and water and each valley provided something different. Todd grabbed his handline and headed to the keyhole through which we had entered. Chris grabbed his collapsible spear and headed to the larger keyhole at the base of the bay. Seth drifted off in a quiet walk in search for water and I, after locating a possible campsite, entered a small patch of jungle in search of fruit. I walked carefully through a small maze of footpaths shadowed by an assortment of trees: swaying coconuts, towering papayas, and dry guava bush. The paths were lined by moss-covered rock walls built centuries ago by the ancient people of this land

I came to an area of obvious importance. The rock walls stood wider and taller and the space that they surrounded was much larger than any of the ones laid before them. The other walls and terraces seemed to lead purposefully toward this one, giving me the undeniable impression of a place of worship. Above this area was a massive gap in the sea of circling trees. It revealed a scene so daunting it sent a chill up my spine. Towering above me was a cliff of a thousand, maybe two-thousand feet high and stretching from top to bottom were gigantic grooves in the shape of an X. They were perfect, as if chiseled out by some giant sculptor. Maybe they were the workings of an ancient god.

I stood there motionless below this overwhelming display I felt its pressure as it leaned its shape upon me. How could Mother Nature create something so out of place, looking so curiously man-made? Maybe it was created by neither and that is why I felt so overwhelmed. I continued my search for fruit, making sure I disturbed nothing.

I stockpiled coconuts for future use. I found guava, shriveled and rotten. The papaya trees were tall and too flimsy to climb and their fruit was a hardened green. I shook a smaller tree containing one ripe papaya and added it to the collection of coconuts. The ground was hard and dry, save for places that never see the sun. The obvious difference between this lonely cove and the others we had previously been to was the dryness. The rain-filled clouds brought forth by wind whipping down the coast seemed to get caught within the steep valley behind us. Once their rain had fallen, they lifted to a higher elevation, thinning as they continued on above us and out to sea.

I brought what I could carry (papaya and coconuts) back through the jungle. Seth was working his way back from the opposite end of the beach, his body dwarfed from the gigantic cliffs surrounding us.

“There’s no water,” he said. He had been to an area where he could view the once-active falls. It was the only possible entry for water in the area.

The sun had dipped over the western wall of the cove putting us beneath its shadow. Todd and Chris returned, Chris looking somewhat unnerved. Since our arrival, Chris had speared two fish, was chased by a 6-foot white tip shark, fed the shark one fish, and chose another venue to work. In the keyhole where Todd was handlining, Chris was swept out with the current and was pushed into a cave—waves bouncing off the ceiling. Because of the slightly bigger swell and outgoing tide, Chris was forced to abandon his spear, swim through the rip, and scale the wave-swept rocks to safety. I listened to the unfortunate details knowing Seth and I had news that would make matters worse.

“The waterfall is dry,” said Seth.

We compared our bottles and all were empty except mine. I had half a liter left.

Chris Malloy:

A wild and woolly ride into the next valley and we were off and running. Everybody had a job to do and I think that, despite a three-hour foraging expedition that morning that yielded nothing, the swim was a confidence builder. The brown rice from last night seems to have put us back in the game.

The swell was building and the tide was dropping. I could see a crack in the reef 50 yards off the beach that soon would be draining the whole lagoon, and I had visions of sticking a big dinner for everybody. Seth was coming back with water, Jeff was scavaging for fruit, and Todd was trolling for crab and shellfish in the tidal zone.

I hit the water, cleared my mask, and sure enough there were fish everywhere. I swam past four or five good eating fish on my way out to the crack and hovered there, confidently enjoying the view. The current was just beginning to surge and I kicked against it with ease waiting and watching, I swam down just below a crack, wedging my knee against a big rock column. A four or five-pound parrot fish swooped back toward me after being flushed out of the lagoon. I’m a bad shot, and I grazed his pectoral fin, sending big blue scales everywhere. I wasn’t worried—certainly there would be more.

Ten minutes later, another came drifting through, only this one decided to take refuge in a shallow cave just across from me. He wasn’t as big, but the shot was too easy and I took it, just behind the gills and all the way to the shaft. I pressed him against the back of the cave and held him there until I got my hand on him. I could almost taste the white meat, and I prayed that they had a fire going by the time I got back to camp. As I kicked to the surface I felt thankful for the safety of the keyhole and felt lucky to find a safe spot to dive with surf that was building into the 6- to 9-foot range. I broke the surface and stuck my hand into the dying fish’s gills.

From below me, almost between my legs came a movement that only one fish makes. She probably smelled me in the water 40 minutes ago. White tip reef sharks are everywhere. They’re curious and, as far as my 20 or 30 encounters go, usually four or five-feet long and easily spooked.

This shark was different—six-feet plus. Fat and pissed. I held my catch out of the water and lunged at it as it made closer and closer passes. My aggression seemed totally unnoticed, and she began twitching and swimming in sprints, her back arched. I poked my head out of the water to assess my distance from the reef and the beach. I made a smooth beeline shoreward with my back to the reef.

Blood from the fish dripped down the shaft of my spear into the water. She made another pass, bumping my fins. Any other day I’d given up the fish ten minutes ago, but all I could think about is all that meat going to waste. She had me beat and flustered. I’d bit through my snorkel without realizing it. I told myself I wasn’t quitting by giving her the fish, and flung it ten feet, watching it splash sending up blood and scales. She bumped it twice then took it in her mouth and powered effortlessly past me, eyeing me and fading into the deep.

Swimming until I got to a smaller crack in the reef, I composed myself and focused on slowing my breathing and making good shots. Within 15 minutes the current began to push harder. It had been a long day and I took a half-hearted shot at a barely edible fish and killed it. Within 30 seconds, the bitch was back, pissed off as ever. Apparently the whole reef was hers and she wanted to make a point of it. By now I had 20 yards to the beach and I made the decision that she would not get this one. She paddled me right up onto the reef until I was standing on it in eight inches of water. At one point, I thought she’d left when she shot up out of the deep, rolling on her side to look me in the eyes. I came up with a few different plans but ended up jumping back in and letting her back-paddle me to the beach. When I was 20 feet from the beach, I catapulted the fish to the sand. She took two final passes and then disappeared for the last time.

Some days water came easy. Tide pool crab became the event of the season.

The surf zone is one of my favorite places to dive. I figured I’d drift for a while, hunting until the current pushed me far enough down the reef that I could swim to the shore through the lagoon. I’d look for octopus on the way in and everything would be just fine. The current had other plans, sucking me toward an 800-foot sea cliff that met the water with a big black sea cave. I kicked softly trying to find a rhythm to the flow but could not find one. For the first time in my life, I could not find the rhythm of the ocean to get me out of a bind and it scared me to the core.

Relaxing and flowing with her had saved me a hundred times, but if I did not kick with all my might I’d be smashed on the ceiling of the cave in just a few minutes. I kicked for 10 or 20 seconds as hard as I could, hoping I might at least get out of the trench and up onto the shallower reef so that I might break for deeper water, but I got nowhere. The only direction the water would allow me to swim was toward the cave. If I waited for the last wave of the next set and swam in with it as it surged, there was a narrow spot covered in urchins. If I timed it right, I thought I might make it. At this point it was my only chance.

I went for it with the last wave of the set. The backwash slapped me in the face, ripping my mask halfway off and disorienting me badly. I took it personally, like I was being toyed with, and the anger began to overtake the fear. The next set came through and I heaved myself up onto the rock face with the swell. I got an elbow into a crack and held on as the water tried to pull me back in. I scrambled with any energy I had left up the face and layed on the ledge staring at the sky.

Jeff Johnson:

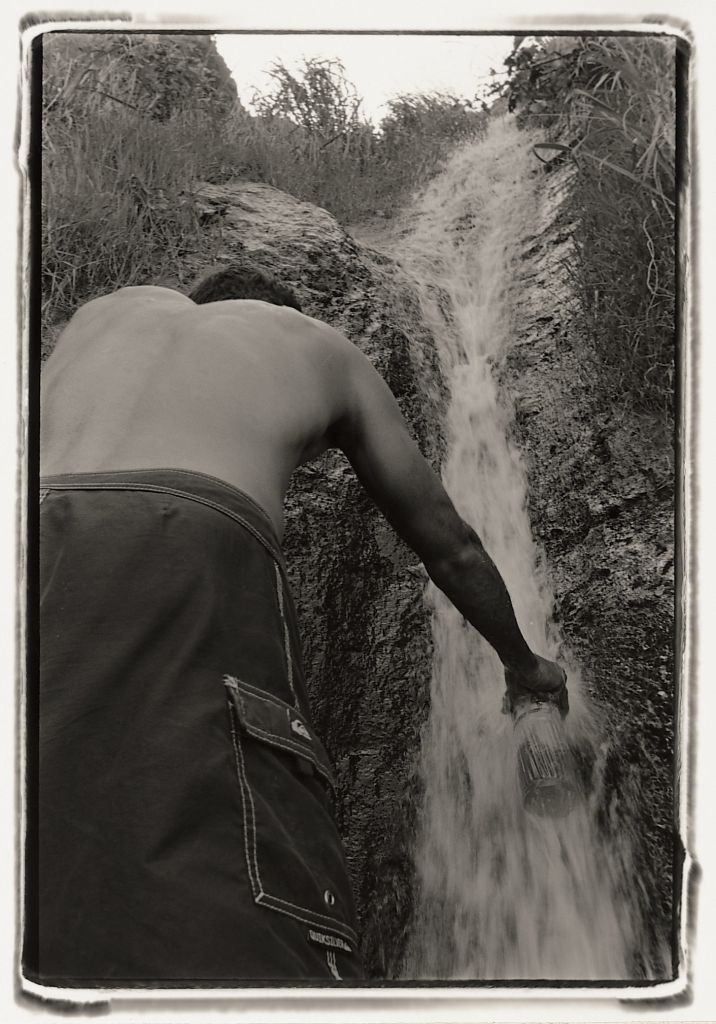

Seth mentioned the goats he saw on a ledge halfway up the falls. Why would these animals congregate in such a precarious zone? A watering hole, perhaps? If the goats could make it….

We had very little light left, so Chris and I donned our headlamps and forged our way up the rocks and through the bush to the base of the falls. We studied the route where the goats had climbed. The trail was loose rock. Below was a vertical drop of about a hundred feet. It looked possible but very dangerous, especially without a rope. Worse, there was no guarantee that water would be up there. We returned to our camp, leaving this idea as the last resort.

There was a possible problem in this trip that we failed to address. So far, the wind and current had been in our favor, but we were told that within this last stretch of coastline the current could change. It’s a random occurrence and could appear at any time, anywhere, and there are no signs, no way of knowing.

Decisions have to be made upon assumption. According to our calculations, there was another valley a mile or so farther down the coast. What if it’s also dry with even less fruit? What if we met the opposing current? What happens when two currents converge? Do you go out to sea? What if the wind turns the other way? Once you pass a valley, there is no going back, so once we leave, we are gone. These thoughts, like pieces of an unseen puzzle, were sprawled out before us.

We had gone to bed with only sips of water, but our conditioned stomachs seemed full. I had worries: four guys working hard all day, very little food, and our water supply was down to less than a half liter. We had an estimated five miles of coast to go and our concerns multiplied. We had some important decisions to make come daybreak.

I slowly drifted into a bizarre stream of waking dreams: black and white, color, dialogue, silence, slow-motion, and so on. As my subconscious rolled on, my physical being took in the new immediate surroundings: wind on my face, sounds in the trees, and the surf. Suddenly an animal, a crab perhaps, scurried across my face. I flailed about as if being attacked by thousands. I was now too frazzled to even think about sleep, so I sat up Indian-style and looked out to the black ocean.

Sometime later, maybe two or three o’clock in the morning, I was startled by something thrashing about my feet. I flung my hands down upon it and found a pool of water rushing all around me. The ocean! The wave receded, pulling its way through the noisy cobblestones and sand. I quickly grabbed my things and made way to higher ground.

The others were now awake. The full moon had finally made its way over the massive cliffs behind us. What used to be lapping little waves at the heel of our camp was now surging shore pound edging its way to where we had once slept. We stood there silent, watching giant piles of whitewater. The outer reefs crumbled under the blue glow of the moon. How big, we did not know. We tried to sleep but couldn’t. With nothing else to do, Todd and Chris made a fire. We gathered around it, warming ourselves, and waited for the dawn.

The morning was bright and calm. The ocean had changed dramatically throughout the night. Large unobstructed swells flexed on the horizon, moving slowly and with purpose. They bended and stretched like waking beasts. From one end of the bay to another, smooth blue walls split themselves into giant peaks, silently hurling their crests toward shore—15, 18, maybe 20 feet.

The swells reformed and doubled-up, turning top to bottom on the inside, sending spit and plumes of spray in all directions. The lagoons would then rise beyond capacity and empty out through the keyhole below. All this violent movement created a river like rip that pushed its way out through the bay and back through the lineup only to be recycled for yet another round.

A school of about 40 to 60 sea turtles had gathered in the keyhole. They seemed to enjoy swimming against the constant flow of water. Occasionally, one would beach itself. It would lie there breathing heavily in the warm rising sun. Then, satisfied as if some goal had been attained, the turtle would flop awkwardly back into the turbulent ocean. The turtle’s peaceful ease and obvious pleasure with the newly-found conditions made me jealous. I wanted to join them.

“Guess we’re not leaving today.”

“Big Mac, fries, and a shake.”

“The swell is getting bigger. I wish I had my 10-footer, and…oh yeah, some water, too.”

“What now?”

All we could do was wait and conserve our energy.

All day we moved slowly and deliberately. We stayed out of the sun and kept all physical activity to a minimum. We lounged around on our mats and daydreamed. Our conversations consisted of questions and theories and debates about our tossing situation: weather, waves, currents, winds, food, water, energy, etc.

After a long rest, Chris decided to return to the dry falls in search of water. He brought a machete to dig at the falls’ muddy base. I offered to go along with him but he declined. It was a one-man job and he didn’t see any point in wasting another’s energy. But that wasn’t the reason I stayed behind. Chris had this look in his eyes. I had seen it before. He has a tendency to worry about others, and if I were to go along he would worry about me. He also doesn’t like people to worry about him, so he wanted to go it alone. This meant he had the freedom to take chances and I didn’t want to deprive him of that right. His look said no, so I stayed and I worried regardless.

Chris returned sometime around noon looking totally beat. He attempted to climb, but was forced to turn back because of loose rock and improper handholds. He dug for hours in the mud at the base of the falls until the hole was big enough to stand in, and he found nothing. I knew by the way he looked that certain details were kept to himself. We gave him some papaya and coconut and he took a tiny sip of water. He made his way to his mat and dropped for a well-deserved afternoon nap

We weren’t in any real danger. Our health was far from being jeopardized and the body can go on for days without food. Aside from occasional discomfort, our health was in good standing. We just didn’t know how long this would last. There were times when all we could think about was food: cokes, milk shakes, burgers, and fries—things I don’t even like became beautiful cravings.

Then there were times of total contentment: not hungry, not thirsty, not anxious, just cool and neutral, maybe even a little euphoric at times, just laying there watching the sky. It’s amazing how the body adjusts. Our stomachs became so small that a spoonful of rice and a chunk of coconut felt like a legitimate meal. But there is no faking the body’s need for water.

We spent the rest of the day within the circumference of our camp. We nibbled on our carefully divided rations and shared stories. When someone spoke up, all would listen. The carefully selected words would linger before us until someone spoke again. From time to time, one of us would move about, rise from the ground, step slowly through the camp, mess with a thing or two, take a bite of coconut, and return once again to the prone position. We waited for nothing in particular or maybe we waited for change.

We wandered around the evening fire watching Todd cook up the last of our brown rice. I sat down and rubbed my hands together in anxious anticipation. We were dirty, thirsty, hungry, and tired. Chris placed the pot of cooked rice between us. He flattened the rice down with a spoon and divided it into quarters. For a moment, we sat there staring at our tiny pie shaped rations. It was almost pathetic. Someone began to laugh and Chris said, “Hey, what’s fair is fair.” We ate slowly, carefully savoring every bite. When dinner was done, we passed around an inch or two of water. Everyone took one good swig.

The amount of food we had for dinner was less than what you’d eat just browsing through the refrigerator. But, it was enough to stop our stomachs from cramping and it kept our minds off food for a while. We rolled onto our mats and stared at the stars.

Chris chose to sleep inside his emergency bag all night—a giant tinfoil-like blanket. Whenever the wind blew or he turned over, it sounded like a giant potato chip bag flapping in the wind.

We crouched under the lee of the tree while Chris stumbled about in his tinfoil gown. He moved from one place to another trying to create makeshift shelters. He’d hover in an area preparing his bedding like a cat preparing to nap. Then he’d be silent, just lying there in the drizzle trying to see if his new home had worked. After a few minutes or so, he’d get up all noisy in the wind and rummage around for a new spot. We watched this routine for quite some time. After his last attempt failed, Chris finally joined us and squalled there in the leaves. His face, a dark hole, was hooded like a monk, or a reaper, or a robed monster. He sat there frozen, defeated, deep in thought.

All of us began to laugh. Somehow, none of this mattered anymore—not the food, not the water, not our uncomfortable bodies. We laughed contagiously while the morning moved on.

The rain turned back into drizzle as the first light began to appear. We made breakfast with leftover papaya and coconut. The clouds moved down the coast at a strong and steady pace. They were low and dark and full of water. The wind was stiff and full of gusts, but in the direction we wanted to go. The waves were in the 6- to 10-foot range and occasionally one would cap on a distant outer reef. The conditions looked comparatively favorable.

We were cleaning up our camp when Todd yelled up from the beach, “Let’s go guys! There is a break in the weather! No time better than the present!”

Within minutes, our campsite was clean and all our possessions stuffed tightly into our dry bags. Duct tape, string, and rope were passed around as we secured our bags to our surf mats. It would be a long day at sea, so we covered our bodies with sunscreen and put Vaseline where chafing was imminent. I noticed my hands were shaking. I was extremely excited. We were finally going to leave this place and move on. A long, beautiful all-day swim! Another valley? Another bay? Once we leave the beach, our day is up for grabs.

I joined the others on the rocks out on the beach. We were skinny, dirty, unshaven, and our skin was dark from too much sun. We looked like a band of refugees: leashes strapped to our ankles, bags lashed to our mats, fins on our feet, goggles on our heads, string and tape hanging everywhere. We were awkward on land, but once we entered the water we would become functional and efficient. We could swim for miles.

I stood there in knee-deep water and looked back at the deserted land. Somehow, it looked different to me. Changed by the day we had landed. But it wasn’t. It was us who had changed. I dove in and opened my eyes. There were 30 or 40 turtles swimming against the flushing sea. They were graceful and slow and their droopy eyes blinked at me with lazy indifference. For a moment, I wallowed within their world and then surfaced again into ours.

We lay on our backs in the middle of the bay, kicking, while our rafts dragged behind. From the cliffs to the sea, a magnificent rainbow had formed. It was a perfect 180 degree arc and its colors were easily defined. We began hooting and hollering in celebration of our departure and this comforting omen. Someone was on our side. We lapsed into a rhythm, stroking steadily out to sea and into the whitecapped wind line. I would lose sight of the others as they dropped into the troughs of open-ocean swell. Occasionally, a whitecap would crash behind me pushing my raft onto my back interrupting my meditative stroke. We were about a quarter of a mile offshore with a strong wind and current in our favor,

We slowly rounded the first point unsure of what we would see. There was a bay with a beach and a valley behind. And beyond this was more of its kind. A seemingly endless array of cliffs, bays, and coves lay ahead. Mist hung eerily between each consecutive ridge line, one after another. We spread ourselves out evenly to match each other’s pace: Stroke, stroke, stoke, breathe. Stroke, stroke, stroke, breathe. I looked up and saw Todd pulling ahead of us. I heard him say something about his mat having a slow leak. Our chart showed a five-mile stretch of water until the next possible landing. I looked out beyond him and down the meandering coast and I could see no end. Stroke, stroke, stroke, and breathe. Stroke and breathe…