San Miguel, the cobble point river mouth just north of Ensenada in Baja California Norte, is a point of origin for Mexican surfing. First regularly ridden in the 1960s by native pioneers Nacho Felix Cota and Carlos Hernandez, the dependable right offers a broad swell window and easy access. Trace the Guadalupe River from its outlet, up a chaparral barranca, and you’ll quickly find yourself in the Valle de Guadalupe. Here on the Ruta del Vino, the pebbled alluvia bears comparison to the flinty terroir of France’s Rhone valley. The climate scans Mediterranean, with the same dusty gray-greens and lavender colorations speckling the sun-cured landscape. This is the site of Tijuana restaurateur and surfer Javier Plascencia’s most recent project, Finca Altozano.

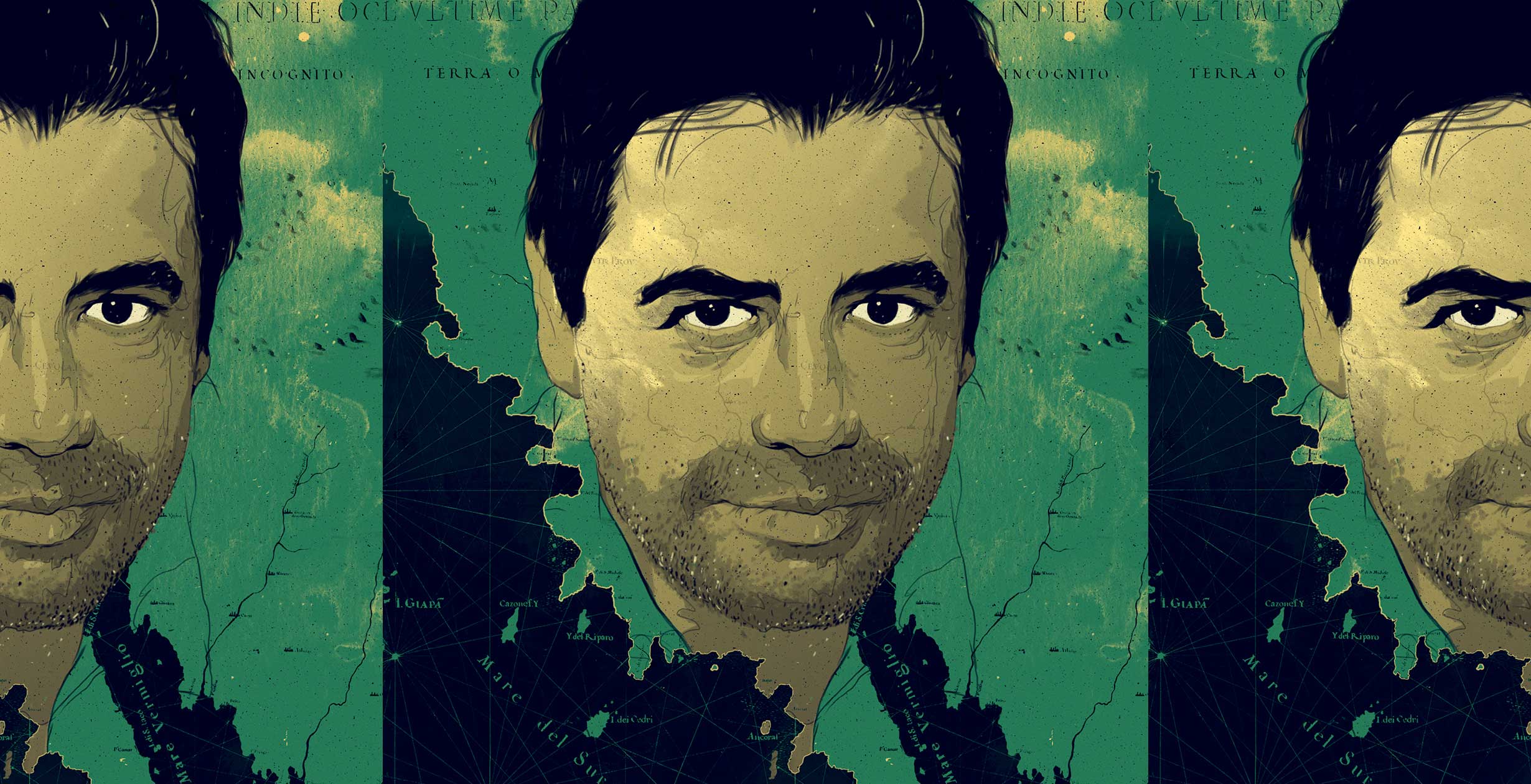

In the decomposed-granite parking lot of this vineyard “camp,” Plascencia keeps a restored trailer for himself and his dog, within earshot of the popular establishment’s proceedings. An ancient, but well-kept, avocado-green Mercedes sedan is parked out front. Plascencia cuts a rugged, understated first impression. Work boots. Vintage Persol shades. Four-day growth. Fifty-one years old at the time of writing, he’s soft-spoken and thoughtful, choosing his responses in a measured way. Like the Nebbiolo and Tempranillo grapes surrounding the Finca, Plascencia comes from well-documented rootstock. Born to the trade, he scurried unabashedly around the various kitchens of his father, learning knife skills and the incalculable value of mise en place. He was a journeyman chef before he could drive a car.

His big break—one that he himself engineered—came in 2011 with the opening of Mision 19, a restaurant that helped define a new international cuisine based on the peninsula’s substantial bounty. “Baja Med” found instant purchase in food media, and the chef found himself unable to hide. The late Anthony Bourdain visited and filmed. Dana Goodyear profiled him with a 12,000-word doorstop in The New Yorker. Pulitzer-winner Jonathan Gold effused over his short rib in fig leaves. With such auspicious notices, the dedicated surfer had placed his dusty, generally lawless border metropolis, Tijuana, squarely in a constellation that includes Lyon, Shanghai, San Sebastian, Puebla, and Bologna—lodestars of gastronomy.

His raw supply chain was discovered during local surf trips. His flavor palette is familiar to any observant Baja wave rider. Maguey (agave) leaves. Rabbit. Yerba buena. Sea urchins. Bluefin tuna. Quail. He merged new-school technique with a Kumeyaay Indian pantry, creating alchemy with mesquite smoke.

While now a household name in culinary circles, Plascencia is hardly doing victory laps. He shuttles between a demanding schedule of business and family operations up and down the peninsula. Surfing vents off the backpressure. Over a plate of charred octopus tostaditas and a local white wine that tastes like a fresh ten-peso coin dropped in a glass of lemon-blossom water, he submitted to our brief grilling.—S.H.

How did you come to surfing?

I was introduced to it in Carlsbad at 16. I went to the Army and Navy Academy. I got kicked out of school in Tijuana, and as punishment my parents sent me there. And I’m very grateful to them because, I mean, I learned about surfing. My room was very close to the beach, walking distance. Every morning for reveille we had to march in our uniforms with rifles. But, I had a great time and my roommate was a surfer. He got me into it.

What was your impression of surfing growing up in Tijuana? Did you see surfers when you went to the beach?

No, not much. When I was, like, 14, I used to take the bus with my friends to Rosarito Beach, and we would bring boogie boards. That was our thing. But I didn’t know about surfing, and I didn’t meet any surfers until I came back from school. My friends that started boogie boarding with me became surfers as well.

Any recollection of your first sled?

It was a Gerry Lopez that the school had for everybody to use. My first personal board that I bought with my own money was from San Miguel Surfboards.

When you came back to Tijuana from Carlsbad, I assume you continued to surf locally…

I did, yeah, yeah, I did. My parents owned a house in Rosarito, and that’s where we started. We built a bar called Coco Loco. And I surfed a lot in Quinta del Mar, right in front of my house. Then, with my friends, I started going to K-38 a lot, and that’s where I, like, really, really fell in love with, you know, the whole life, and met the real locals that were there back in the 80s.

I have a pet theory that Mexico might be the most naturally gifted country for surfing on earth. From Todos to Salina Cruz, from Scorpion to Puerto Escondido to Pascuales. Pound-for-pound it’s worth considering. What is your impression of the national surf resource?

I travel a lot throughout the world, and I always try to go surfing, but it’s often crowded or flat or cold. Even though there are many more local surfers and tourists coming to surf now, you can usually find an empty wave in Mexico. And you still get that Baja vibe, which is very rural and third world.

I mean, I agree with you. I’ve surfed all over Baja. I’ve been to Oaxaca several times, down to Escondido, I’ve been to Michoacan. I travel a lot throughout the world, and I always try to go surfing, but it’s often crowded or flat or cold. Even though there are many more local surfers and tourists coming to surf now, you can usually find an empty wave [in Mexico]. And you still get that Baja vibe, which is very rural and Third World. It’s just hard to get anywhere. You still feel like you’ve discovered something really amazing. It’s something that when you just talk about it, it’s very different. You have to live it.

Where do you surf these days?

Well now, I love K-38 because it’s such a fun wave and it’s perfect for my surfing. I don’t surf big waves. I like Popotla. The left is very, very fun. Those two places, and El Morro. We have a villa at K-38, so it’s very easy for us to go there. It’s where we keep our equipment, and where we do all of the friends and family things. Now, our family comes, our kids come, and we have big gatherings and surf and do carne asada. When I went there as a kid—after they started building those condominiums—they would kick us out. They wouldn’t allow us in. Eventually, we made friends with the guards. But when I saw those, I said, “Fuck, I wish I could buy a place so I can just surf here all my life.” And, now it’s become true. We have a cam and we can watch it from the kitchen in the restaurant. So, we know when it’s good.

Do you know anything about the surfing history of Baja, such as it is? Juan Hussong and Ricardo Dominguez and that first generation of locals?

I know them, and I talk to them. Like, Jacinto, he still owns a surf shop in Rosarito. All those guys that were locals at that time, when we were growing up, we looked up to them, and they were like our idols. They were hardcore. There are several guys that I’ve seen lately that still surf sometimes.

What do you think about the idea of Tijuana as a surf city, with Playas and the world-class beachbreak at Baja Malibu just minutes away?

Definitely in Playas. I think it is the biggest surf community in Baja, if you find all those kids that live there, because it’s so close. A lot of kids walk or take their bike. I used to surf there a lot when I had my restaurant in Plaza Fiesta in Zona Rio. I’d wake up early in the morning and go surf Playas and then come back to the restaurant. Some of my friends go there and surf in the afternoons when they get off work. I mean, we used to go surf Rosarito and come back fast and get back to work. Now, it’s very hard because it’s growing so much. It’s very urbanized now. So, there are a lot of people going and coming back after work.

Sure, like any big city. But you’re proof of it. A surfer could live in Tijuana, and get all the benefits of that vibrancy and action and food and the art scene, and maintain a surfing life too—at a quarter of the cost of San Diego.

Totally. A lot of surfers love to come to Tijuana and have a good time. I mean, it’s always been like that. I think surfers now are, you know, more cultural. They’re not like the surfers that used to come and drink cheap beer. Now, they smoke better weed, and they drink better beers, and they’re into wine, and they’re into food, and it’s just fun. I mean, when I’m in the lineup, that’s what I talk about with friends, or with the people that recognize me, or that go to my restaurants.

What’s a go-to after-surf meal for an internationally renowned chef? I mean, if you’ve had a two-session day and you’re just ruined. What do you think of when you come home? What do you want to eat?

I want to eat mostly seafood, like tostadas, like ceviche, like fish tacos. That’s what I crave—and a really good beer or a wine. Sometimes pizza.

Your family’s pizza connection vibrates for me. When my great grandparents came to San Diego in the 1940s, their go-to restaurant was Filippi’s Cash and Carry on India Street. That’s been our family joint ever since. And, your dad, obviously, had a connection to that shop. That’s kind of the beginning of the dynasty, right?

Yeah, he learned to make pizza just sitting on the counter there in Little Italy. And he opened the first pizzeria in Tijuana back in ’68. So, it’s going to be 50 years almost. But, [the Tijuana version] is Giuseppe style, like New York style, and that flavor is very stuck in me. So, when I get the munchies, that’s where I go.

The chefs that are doing Baja-style cooking are taking the time to learn what ingredients people used to cook with, and how they cooked. So, we learned that all the natives cooked with wood—live fire, because there was no gas. So, they used mesquite or any wood that they could find. And, they charred a lot of stuff. They cooked abalone and lobsters right on the fire.

Indigenous Baja foods like roasted agave tips and wild honey, chocolate clams, pitahaya, venison, things like that…does that maintain a presence in modern Baja cooking?

Yeah, a lot. The chefs that are doing Baja-style cooking are taking the time to learn what ingredients people used to cook with, and how they cooked. So, we learned that all the natives cooked with wood—live fire, because there was no gas. So, they used mesquite or any wood that they could find. And, they charred a lot of stuff. They cooked abalone and lobsters right on the fire. That’s why when you taste Baja cuisine, there is always some type of smokiness. They have to be cooked on fire or charcoal, or it doesn’t taste authentic for us. But, yeah, they cook with a lot of flour tortillas in the northern part of Baja, not a lot of corn. Lots of deer. Quail was big around this area. Rabbit too. They used to eat horsemeat as well. All the machacas are very popular in the north of Baja California. So, they make machaca with lobster, and machaca with shrimp and fish. I remember when I was growing up, every Sunday, my father took us to this place where he ate caguama (turtle) soup. That was a big thing for him on Saturday or Sunday, I think because he’d be kind of hung over. I remember I couldn’t handle it at the time. That smell was kind of very strong for me. But, he took us, and I still remember how he enjoyed it. I learned to eat it, and I enjoyed it when I was a little bit older, in my twenties. Now it’s illegal, but I still remember that smell, and that flavor. So, we make “caguama soup” today, but it’s made with manta ray and tuna. Another truly Baja ingredient would be totuava—those big, oily cuts of fish from San Felipe—but now we get that farmed. And, also the abalones. It’s something that’s going away. You can still find it, but nowadays cooks are learning to work with farm-raised abalone. We support those companies, because I think it’s very important to preserve what we have still in the ocean and not to overfish it. But, like my kids, they don’t know what a big abalone tastes like, or they’ve never seen it big, the way I saw it when I was a kid. Also, lobsters. It’s farm-raised. It’s still good, but it’s not the same.

How do you break up your time between your businesses in Tijuana and Todos Santos and here in the Valle?

Well, when you’re away, it’s not always going to be the same as if you are here all the time taking care of stuff. I mean, I just got here and I saw ten things that I really was disappointed with. I just took my guys and said, “Come on, what’s going on.” But I use phones, cameras. I run six restaurants that are under my name, but also my family runs thirteen restaurants that I help out, you know, with events, and menus, and that kind of stuff. Plus, I do seminars, and talks, and cooking demos— those kind of events. So, it’s tough. I’m in and out. I’m on airplanes a lot. What hurts most, what I don’t like about this, is that it takes a lot of time away from my kids, and also from surfing. But it’s my passion. You have to have really good people. I mean, any business, but especially in this hospitality business, you have to have a very, very, good staff. They are part of the family. We take really good care of our managers and our chefs. We travel with them. They run the show. So I can go surfing.

What class of tequila do you favor?

I am more of a Mezcal drinker. I prefer the ones from Durango.

Illustration by Simon Prades. Reference photo by Matt Suarez.